PPEcel

cope and seethe

★★★★★

- Joined

- Oct 1, 2018

- Posts

- 29,087

Three weeks ago, a three-judge panel of the U.S. Court of Appeals of the Eleventh Circuit unanimously ruled in favor of three sex offenders whose First Amendment rights were violated by the sheriff of Butts County, Georgia.

You can read the full decision here:

Background

In October 2018, Sheriff Gary Long instructed his deputies to place the following sign in front of the homes of all 50+ registered sex offenders under his jurisdiction. The sign was accompanied by a pamphlet that stated (incorrectly) that sex offenders in Georgia were not allowed to celebrate Halloween, and that removing the sign would lead to their arrest.

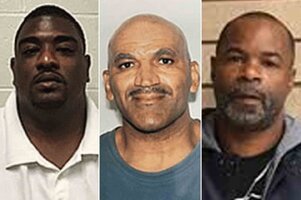

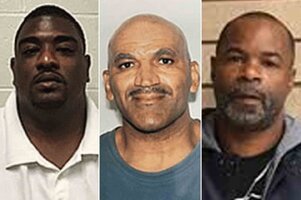

Three sex offenders, Corey McClendon, Reginald Holden, and Christopher Reed, soon filed a federal class action lawsuit alleging that the sheriff violated their First Amendment rights.

While the federal district judge granted a preliminary injunction in their favor, the same judge later ruled that no First Amendment rights were violated and granted summary judgment in favor of Long, arguing that the signs were covered under the government speech doctrine, not the compelled speech doctrine.

Compelled Speech Doctrine

The Eleventh Circuit disagreed. The district court's judgment was reversed. Their reasoning was simple: the First Amendment “includes both the right to speak freely and the right to refrain from speaking at all.” Wooley v. Maynard, 430 U.S. 705, 714 (1977).

The compelled speech doctrine dates back to West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette, 319 U.S. 624 (1943). In Barnette, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that it was unconstitutional to force schoolchildren to recite the pledge of allegiance. "If there is any fixed star in our constitutional constellation, it is that no official, high or petty, can prescribe what shall be orthodox in politics, nationalism, religion, or other matters of opinion, or force citizens to confess by word or act their faith therein." Id. The federal courts have since considerably expanded this principle in the intervening decades.

Noting that the sheriff cited exactly zero instances where a registered sex offender in his county utilized trick-or-treating or Halloween as a ploy to commit sexual assault, the appeals court held that Long's actions easily failed strict scrutiny.

The Eleventh Circuit understood what should be common sense to everyone who even remotely understands First Amendment jurisprudence: it is plainly unconstitutional for the government to coerce a private individual into conveying the government's speech. By forcing sex offenders to place a yard sign whose content they disagreed with, on their property, the sheriff blatantly violated the First Amendment.

Why do I care about this case, you ask? The answer is simple: civil liberties are counter-majoritarian. There is no need to defend popular speech or popular individuals. By upholding the plaintiffs' First Amendment rights despite their unpopularity, the federal judiciary reaffirmed its commitment to the rule of law, as opposed to the rule of the soycuck mobs.

Based federal appeals court judgecels!

You can read the full decision here:

Background

In October 2018, Sheriff Gary Long instructed his deputies to place the following sign in front of the homes of all 50+ registered sex offenders under his jurisdiction. The sign was accompanied by a pamphlet that stated (incorrectly) that sex offenders in Georgia were not allowed to celebrate Halloween, and that removing the sign would lead to their arrest.

Three sex offenders, Corey McClendon, Reginald Holden, and Christopher Reed, soon filed a federal class action lawsuit alleging that the sheriff violated their First Amendment rights.

While the federal district judge granted a preliminary injunction in their favor, the same judge later ruled that no First Amendment rights were violated and granted summary judgment in favor of Long, arguing that the signs were covered under the government speech doctrine, not the compelled speech doctrine.

Compelled Speech Doctrine

The Eleventh Circuit disagreed. The district court's judgment was reversed. Their reasoning was simple: the First Amendment “includes both the right to speak freely and the right to refrain from speaking at all.” Wooley v. Maynard, 430 U.S. 705, 714 (1977).

The compelled speech doctrine dates back to West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette, 319 U.S. 624 (1943). In Barnette, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that it was unconstitutional to force schoolchildren to recite the pledge of allegiance. "If there is any fixed star in our constitutional constellation, it is that no official, high or petty, can prescribe what shall be orthodox in politics, nationalism, religion, or other matters of opinion, or force citizens to confess by word or act their faith therein." Id. The federal courts have since considerably expanded this principle in the intervening decades.

Noting that the sheriff cited exactly zero instances where a registered sex offender in his county utilized trick-or-treating or Halloween as a ploy to commit sexual assault, the appeals court held that Long's actions easily failed strict scrutiny.

The Eleventh Circuit understood what should be common sense to everyone who even remotely understands First Amendment jurisprudence: it is plainly unconstitutional for the government to coerce a private individual into conveying the government's speech. By forcing sex offenders to place a yard sign whose content they disagreed with, on their property, the sheriff blatantly violated the First Amendment.

Why do I care about this case, you ask? The answer is simple: civil liberties are counter-majoritarian. There is no need to defend popular speech or popular individuals. By upholding the plaintiffs' First Amendment rights despite their unpopularity, the federal judiciary reaffirmed its commitment to the rule of law, as opposed to the rule of the soycuck mobs.

Based federal appeals court judgecels!