InMemoriam

Acktually 2020cel

★★★★★

- Joined

- Feb 19, 2022

- Posts

- 10,300

View: https://www.reddit.com/r/beauty/comments/qluorr/is_it_rare_to_look_actually_good_with_no_make_up/?utm_source=share&utm_medium=web2x&context=3

I would say only about 10% to 20% of women are still attractive without makeup. Just like chads are very rare for men naturally beautiful women are pretty rare as well

Is there a real natural female beauty? or is it just facial beautification?

well a 2019 based study said to have ''revealed'' sex-specific genetic architecture of facial attractiveness; however the researchers has not examined influence factors such as cosmetics and facial beautification, so the questions remain unanswered

In our study, each photo was rated by 12 different coders and the rating scores were consistent across coders. These results suggest the robustness of the phenotypic measurements in our study, but many questions remain unanswered. What are the roles of age, physical body shape, facial expression, and make-up in the perception of attractiveness? What is the impact of assortative mating on the genetics of attractiveness [50]? And what is the shared and distinct genetics between attractiveness and closely related facial phenotypes such as symmetry, averageness, and sexually dimorphic features [14]? These are just a handful of questions beyond the scope of this study.

another similarly interesting study which was conducted back in 2011 aimed to investigate the role of cosmetics as a Feature of the Extended Human Phenotype

implications of the study as summarized in a now 11 years old new york times article:Abstract Research on the perception of faces has focused on the size, shape, and configuration of inherited features or the biological phenotype, and largely ignored the effects of adornment, or the extended phenotype. Research on the evolution of signaling has shown that animals frequently alter visual features, including color cues, to attract, intimidate or protect themselves from conspecifics. Humans engage in conscious manipulation of visual signals using cultural tools in real time rather than genetic changes over evolutionary time. Here, we investigate one tool, the use of color cosmetics. In two studies, we asked viewers to rate the same female faces with or without color cosmetics, and we varied the style of makeup from minimal (natural), to moderate (professional), to dramatic (glamorous). Each look provided increasing luminance contrast between the facial features and surrounding skin. Faces were shown for 250 ms or for unlimited inspection time, and subjects rated them for attractiveness, competence, likeability and trustworthiness. At 250 ms, cosmetics had significant positive effects on all outcomes. Length of inspection time did not change the effect for competence or attractiveness. However, with longer inspection time, the effect of cosmetics on likability and trust varied by specific makeup looks, indicating that cosmetics could impact automatic and deliberative judgments differently. The results suggest that cosmetics can create supernormal facial stimuli, and that one way they may do so is by exaggerating cues to sexual dimorphism. Our results provide evidence that judgments of facial trustworthiness and attractiveness are at least partially separable, that beauty has a significant positive effect on judgment of competence, a universal dimension of social cognition, but has a more nuanced effect on the other universal dimension of social warmth, and that the extended phenotype significantly influences perception of biologically important signals at first glance and at longer inspection.

Up the Career Ladder, Lipstick In Hand [2011]

In a study, women were photographed wearing varying amounts of makeup, from left: barefaced, natural, professional and glamorous. Viewers considered the women wearing more makeup to be more competent.

By Catherine Saint Louis

WANT more respect, trust and affection from your co-workers?

- Oct. 12, 2011

Wearing makeup — but not gobs of Gaga-conspicuous makeup — apparently can help. It increases people’s perceptions of a woman’s likability, her competence and (provided she does not overdo it) her trustworthiness, according to a new study, which also confirmed what is obvious: that cosmetics boost a woman’s attractiveness.

It has long been known that symmetrical faces are considered more comely, and that people assume that handsome folks are intelligent and good. There is also some evidence that women feel more confident when wearing makeup, a kind of placebo effect, said Nancy Etcoff, the study’s lead author and an assistant clinical professor of psychology at Harvard University (yes, scholars there study eyeshadow as well as stem cells). But no research, till now, has given makeup credit for people inferring that a woman was capable, reliable and amiable.

The study was paid for by Procter & Gamble, which sells CoverGirl and Dolce & Gabbana makeup, but researchers like Professor Etcoff and others from Boston University and the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute were responsible for its design and execution.

The study’s 25 female subjects, aged 20 to 50 and white, African-American and Hispanic, were photographed barefaced and in three looks that researchers called natural, professional and glamorous. They were not allowed to look in a mirror, lest their feelings about the way they looked affect observers’ impressions.

One hundred forty-nine adults (including 61 men) judged the pictures for 250 milliseconds each, enough time to make a snap judgment. Then 119 different adults (including 30 men) were given unlimited time to look at the same faces.

The participants judged women made up in varying intensities of luminance contrast (fancy words for how much eyes and lips stand out compared with skin) as more competent than barefaced women, whether they had a quick glance or a longer inspection.

“I’m a little surprised that the relationship held for even the glamour look,” said Richard Russell, an assistant professor of psychology at Gettysburg College in Gettysburg, Pa. “If I call to mind a heavily competent woman like, say, Hillary Clinton, I don’t think of a lot of makeup. Then again, she’s often onstage so for all I know she is wearing a lot.”

However, the glamour look wasn’t all roses.

“If you wear a glam look, you should know you look very attractive” at quick glance, said Professor Etcoff, the author of “Survival of the Prettiest” (Doubleday, 1999), which argued that the pursuit of beauty is a biological as well as a cultural imperative. But over time, “there may be a lowering of trust, so if you are in a situation where you need to be a trusted source, perhaps you should choose a different look.”

Just as boardroom attire differs from what you would wear to a nightclub, so can makeup be chosen strategically depending on the agenda.

“There are times when you want to give a powerful ‘I’m in charge here’ kind of impression, and women shouldn’t be afraid to do that,” by, say, using a deeper lip color that could look shiny, increasing luminosity, said Sarah Vickery, another author of the study and a Procter & Gamble scientist. “Other times you want to give off a more balanced, more collaborative appeal.”

In that case, she suggested, opt for lip tones that are light to moderate in color saturation, providing contrast to facial skin, but not being too glossy.

But some women did not view the study’s findings as progress.

“I don’t wear makeup, nor do I wish to spend 20 minutes applying it,” said Deborah Rhode, a law professor at Stanford University who wrote “The Beauty Bias” (Oxford University Press, 2010), which details how appearance unjustly affects some workers. “The quality of my teaching shouldn’t depend on the color of my lipstick or whether I’ve got mascara on.”

She is no “beauty basher,” she said. “I’m against our preoccupation, and how judgments about attractiveness spill over into judgments about competence and job performance. We like individuals in the job market to be judged on the basis of competence, not cosmetics.”

But Professor Etcoff argued that there has been a cultural shift in ideas about self adornment, including makeup. “Twenty or 30 years ago, if you got dressed up, it was simply to please men, or it was something you were doing because society demands it,” she said. “Women and feminists today see this is their own choice, and it may be an effective tool.”

Dr. Vickery, whose Ph.D. is in chemistry, added that cosmetics “can significantly change how people see you, how smart people think you are on first impression, or how warm and approachable, and that look is completely within a woman’s control, when there are so many things you cannot control.”

Bobbi Brown, the founder of her namesake cosmetics line, suggested that focusing on others’ perceptions misses the point of what makes makeup powerful.

“We are able to transform ourselves, not only how we are perceived, but how we feel,” she said.

Ms. Brown also said that the wrong color on a subject may have caused some testers to conclude that women with high-contrasting makeup were more “untrustworthy.” “People will have a bad reaction if it’s not the right color, not the right texture, or if the makeup is not enhancing your natural beauty,” she said.

Daniel Hamermesh, an economics professor at the University of Texas at Austin, said the conclusion that makeup makes women look more likable — or more socially cooperative — made sense to him because “we conflate looks and a willingness to take care of yourself with a willingness to take care of people.”

Professor Hamermesh, the author of “Beauty Pays” (Princeton University Press, 2011), which lays out the leg-up the beautiful get, said he wished that good-looking people were not treated differently, but said he was a realist.

“Like any other thing that society rewards, people will take advantage of it,” he said of makeup’s benefits. “I’m an economist, so I say, why not? But I wish society didn’t reward this. I think we’d be a fairer world if beauty were not rewarded, but it is.”

what an interesting 11 years old blackpill!, right?

here are some scientific reasoning onto why feminoids wear makeup religiously;

- women use makeup as a tactic to attract mates and compete with rivals[2020] (water is wet it seems, at least around here

)

ABSTRACT Appearance alterations are an important part of human history, culture, and evolution that can serve many functions. Cross-culturally, women more than men use makeup as a specific, temporary, personalized, and relatively accessible technique for appearance alteration. Women wear makeup to attract attention and/or to mask their imperfections, and indeed, made-up women are on average perceived as more attractive, healthy, promiscuous, and as having higher prestige. Makeup use can thus be related not only to potential partner attraction but also to a rival competition. We aimed to test whether makeup usage in women is predicted by evolutionary relevant factors such as self-reported mate value or intrasexual competition. In total, 1344 Brazilian women responded online about frequency of makeup usage, money spent on makeup per month, and time spent applying makeup per day. They further reported their mate value, intrasexual competition, age, relationship status, reproductive status, sociosexuality, and income. Exploratory correlations and the final regression models indicate that age, intrasexual competition, and mate value positively predict makeup usage. Thus, makeup usage may have a dual evolutionary utility, serving as a behavioral tactic of both intersexual attraction –including alteration of age perception– and intrasexual competition.

so why cosmetics works and [who?] is behind it!

The effects of makeup on behavioral measures

Current research has attempted to empirically assess several effects of facial makeup. Morikawa and colleagues have used a psychophysical method and have revealed that observers perceived the eyes as larger in a photograph of a female model who applied eyeliner, mascara, or eye shadow compared to the photograph of a female model without any eye makeup, even though actual eye sizes were completely identical [6, 7].

These findings suggest that facial makeup alters the perception of facial features in the same way as geometrical visual illusions. From the perspective of facial recognition, Ueda and Koyama [8] and Tagai et al. [9] found that facial makeup affects the judgment of recognizing the facial images of the same person. The facial images had three different styles of makeup: light (softer), heavy (more glamorous), and no makeup. Ueda and Koyama [8] reported that faces with light makeup were more accurately recognized than those without makeup, whereas heavy makeup decreased the accuracy of facial recognition.

Contrastingly, Tagai et al. [9] reported that faces wearing light and heavy makeup had worse accuracy than those without makeup. Although their results were conflicting, their findings suggest that facial makeup alters the recognition of facial identity. A series of previous studies have supported the positive effects of makeup on perceived facial attractiveness. Both male and female observers rated faces with makeup as more attractive than faces without makeup [10–18]. This appearance-enhancing effect has been repeatedly confirmed, both with self-applied makeup [10, 14, 16–18] and professionally applied makeup [9, 11–13, 15, 18].

Additionally, the Implicit Association Test (IAT) revealed that makeup use is subconsciously associated with positive evaluations [19]. Furthermore, the effects of makeup are not limited to the perceptions of others’ faces and also affect the perception of one’s own face [10, 16]. In a study reported by Cash et al. [10], women believed that facial makeup made them more attractive. Additionally, they showed that women tended to overestimate the attractiveness of their own faces with makeup compared to their peers’ evaluations while underestimating those without makeup.

Palumbo et al. [16] assigned female undergraduates to one of three manipulation groups: makeup, face-coloring, and music listening groups. The participants assigned to the makeup group were asked to apply makeup by themselves, those assigned to the face-coloring group were asked to color a schematic face, and those assigned to the music listening group were asked to listen to a music excerpt by Mozart. All participants were asked to rate their degree of self-perceived attractiveness before and after each manipulation.

The authors found that only participants assigned to the makeup group reported an improvement in self-perceived attractiveness after the manipulation. The evidence we have reviewed thus far suggests that facial makeup modifies how faces look at both perceptual and cognitive stages, and the effects extend to how we see our own faces.

It is perhaps unsurprising that the color red has been a popular choice for lipstick since antiquity (Regas and Kozlowski, 1998). The red-green contrast of the mouth, exaggerated by cosmetics, may function as a supernormal stimulus, cueing not only youth, but also information about sexual intent.

Given that the use of cosmetics by women enhances their facial contrast, making them appear more feminine, it is unsurprising that women use cosmetics as a primary method of enhancing appearance for initiating relationships (Greer and Buss, 1994), and receive more male attention when wearing cosmetics (Guéguen, 2008).

The above evidence might suggest that cosmetics function as supernormal stimuli, exaggerating feminine traits. In non-human animals, exaggerated sexual characteristics, such as lengthened tails (Winquist and Lemon, 1994), lead to greater mating success.

Though the lack of a sex difference in mouth contrast was surprising, and does not support the notion that cosmetics serve to enhance sexually dimorphism in facial contrast, the present results confirm that cosmetics can serve to make female faces appear supernormal by exaggerating attractive contrasts (e.g. reddened lips, Stephen and McKeegan, 2010).

These findings indicate cosmetics can increase attractiveness by acting on multiple facial signal channels, such as those of youth and femininity

supernormal stimuli and the concept of neoteny: below a non-cucked super based explanation for two phenomena ; quoting the based work of MRA author peter wright in his based book ''gynocentrism from feudalism to the modern disney princess [2014]: (would make a book review soon; maby)

A superstimulus refers to the exaggeration of a normal stimulus to which there is an existing biological tendency to respond. An exaggerated response, or, if you will, superresponse, can be elicited by any number of superstimuli.

For example, when it comes to female birds, they will prefer to incubate larger, artificial eggs over their own natural ones.

Large, colorful eggs are a superstimulus. Leaving real eggs out to die is the superresponse.

Similarly, humans are easily exploited by junk food merchandisers. Humans are easily trained to choose products that cause heart disease, diabetes, and cancer over the nutritious food they evolved to eat and thrive on, simply by playing tricks on the taste buds and manipulating the starvation reflex.

Sugar and refined carbohydrates are superstimuli. Consuming toxic substances is the superresponse.

The idea is that healthy human behavior evolved in response to normal stimuli in our ancestor’s natural environment. That includes our reproductive instincts. The same behavioral responses have now been hijacked by the supernormal stimulus.1

From this perspective, we see that a superstimulus acts like a potent drug, one every bit comparable to heroin or cocaine which imitate weaker chemicals like dopamine, oxytocin, and endorphins, all of which occur naturally in our bodies.

As with drug addictions, the effects of superstimuli account for a range of obsessions and failures plaguing modern man – from the epidemic of obesity and obsessions with territoriality to the destructive, violent and suicidal behaviors central to our modern cult of romantic love.

An interesting tidbit about superstimuli of manufactured narcotics is the phenomenon known as “chasing the dragon.” It is a term that originated in the opium dens of China, and it refers to what happens the first time a person inhales opium vapor. The resulting euphoria is complete, even magical — the first time.

Subsequent to that, the user tries again and again, with ever-increasing amounts of the drug, to re-create that first blissful high. They can’t do it. The brain is now familiar with the flood of manufactured opiates. The user gets high and very addicted, but the magic of the first experience is an elusive butterfly.

They pursue it, though, with all their might, chasing the dragon they rode in their first experience.

We see a similar phenomenon with men trying desperately in their relationships with women to be rewarded with redeeming love, sex and approval, through the use of romantic chivalry. It sends them, like an addict, traveling the path of a Mobius strip, going in circles, chasing the dragon.

There is little doubt in our minds how this happens.

Here are three examples of human superstimuli, and how they are used to elicit a destructive superresponse in the human male.

Artificially manufactured neoteny

Neoteny is the retention of juvenile characteristics in body, voice or facial features. In humans, neoteny activates what is known as the parental brain, or the state of brain activity that promotes nurturance and caretaking. The activation occurs through something called an innate releasing mechanism.

A classic example of an innate releasing mechanism is when seagull chicks peck at the parent’s beak to get food.

Each adult seagull has a red spot on the underside of their beak, the sight of which instinctively triggers, or releases, the chicks to peck. It is the innate releasing mechanism.

This innate releasing mechanism, of course, is essential to the survival of seagulls, and there is something like it to be found in all birds and mammals — any creature that cares for its offspring. In mammals, juvenility is one of the innate releasing mechanisms that unconsciously determine our motivations to protect and provide, thus ensuring the survival of the species.

Juvenile characteristics in humans, however, can also be manipulated to garner attention and support that far exceeds the demands of survival.

In particular, neoteny is exploited by women to gain various advantages, a fact not lost on medical doctor and author Esther Vilar, who writes:

Woman’s greatest ideal is a life without work or responsibility – yet who leads such a life but a child? A child with appealing eyes, a funny little body with dimples and sweet layers of baby fat and clear, taut skin – that darling minature of an adult. It is a child that woman imitates – its easy laugh, its helplessness, its need for protection. A child must be cared for; it cannot look after itself. And what species does not, by natural instinct, look after its offspring? It must – or the species will die out.

With the aid of skillfully applied cosmetics, designed to preserve that precious baby look; with the aid of helpless exclamations such as ‘Ooh’ and ‘Ah’ to denote astonishment, surprise, and admiration; with inane little bursts of conversation, women have preserved this ‘baby look’ for as long as possible so as to make the world continue to believe in the darling, sweet little girl she once was, and she relies on the protective instinct in man to make him take care of her.” 2

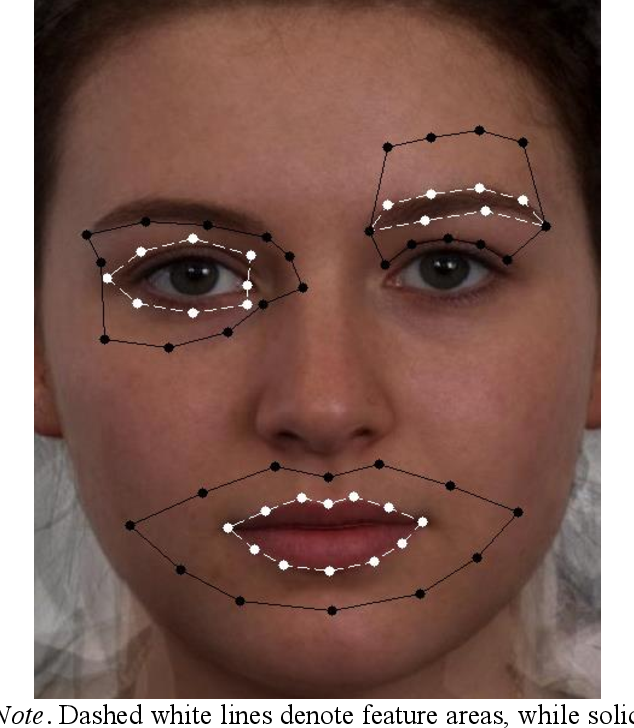

Zoologist Konrad Lorenz discovered that images releasing parental reactions across a wide range of mammalian species were rounded heads and large eyes (left), compared with angular heads with proportionally smaller eyes that do not elicit such responses.

Compare Lorenz’s images on the left with images of skilfully applied eye makeup above by the modern woman in search of romance. The many colored eyeshadows, eyeliners, and mascaras, not to mention the hours practiced in front of the mirror opening those eyes as wide as possible and fluttering – all designed to spur the viewer’s paleo reflexes into action.

Neotenic female faces (large eyes, greater distance between eyes, and small noses) are found to be more attractive to men while less neotenic female faces are considered the least attractive, regardless of the females’ actual age.3 And of these features, large eyes are the most effective of the neonate cues4 – a success formula utilized from Anime to Disney characters in which the eyes of adult women have been supersized and faces rendered childish.

how do women employ neoteny to achieve their goals?

View: https://www.reddit.com/r/Splendida/comments/ndscl5/neoteny_the_biology_of_attractiveness/?utm_source=share&utm_medium=web2x&context=3

View: https://www.reddit.com/r/Splendida/comments/meckff/using_makeup_to_appear_more_neotenous/?utm_source=share&utm_medium=web2x&context=3

Abstract

Makeup accentuates three youth-related visual features – skin homogeneity, facial contrast, and facial feature size. By manipulating these visual features, makeup should make faces appear younger. We tested this hypothesis in an experiment in which participants estimated the age of carefully controlled photographs of faces with and without makeup. We found that 40- and especially 50-year-old women did appear significantly younger when wearing makeup. Contrary to our hypothesis, 30-year-old women looked no different in age with or without makeup, while 20-year-old women looked older with makeup. Two further studies replicated these results, finding that makeup made middle-aged women look younger, but made young women look older. Seeking to better understand why makeup makes young women look older, we ran a final study and found evidence that people associate makeup use with adulthood. By activating associations with adulthood, makeup may provide an upward bias on age estimations of women who are not clearly adult. We propose that makeup affects social perceptions through bottom-up routes, by modifying visual cues such as facial contrast, facial feature size, and skin homogeneity, and also through top-down routes, by activating social representations and norms associated with makeup use.

Abstract While a number of studies have investigated the effects of makeup on how people are perceived, the vast majority have used professionally applied makeup. Here, we tested the hypothesis that professional makeup is more effective than self-applied makeup. We photographed the same target women under controlled conditions wearing no makeup, makeup they applied themselves, and makeup applied by professional makeup artists. Participants rated the faces as appearing more attractive, more feminine, and as having higher status when wearing professional makeup than self-applied makeup. Secondarily, we found that participants perceived the professional makeup as appearing heavier and less natural looking than the self-applied makeup. This work shows that professional makeup is more effective than self applied makeup and begins to elucidate the nature of makeup artistry. We discuss these findings with respect to personal decoration and physical attractiveness, as well as the notion of artists as experts.

In conclusion, our results provide the first empirical evidence that professional makeup is more effective than self-applied makeup and quantities the value added by aesthetic professionals. This has implications for the choice of professional or self-applied makeup in future research examining the effects of cosmetics on person perception. While most of this literature has investigated how the presence or absence of makeup affects person perception, our findings show that different kinds of cosmetic application can have different effects person perception.

basically the heavier unnatural aka pornstar makeup the better

something looks like this:

below is ex pornstar veronica vain tutorial on this so called ''pornstar makeup'' for research purposes

View: https://youtu.be/39aR_XrQ_G4

Abstract Makeup is a prominent example of the universal human practice of personal decoration. Many studies have shown that makeup makes the face appear more beautiful, but the visual cues mediating this effect are not well understood. A widespread belief holds that makeup makes the facial features appear larger. We tested this hypothesis using a novel reference comparison paradigm, in which carefully controlled photographs of faces with and without makeup were compared with an average reference face. Participants compared the relative size of specific features (eyebrows, eyes, nose, mouth) of the reference face and individual faces with or without makeup. Across three studies we found consistent evidence that eyes and eyebrows appeared larger with makeup than without. In contrast, there was almost no evidence that the lips appeared larger with makeup than without. In two studies using professionally applied makeup the nose appeared smaller with makeup than without, but in a study using self-applied makeup there was no difference. Thus makeup was found to alter the facial feature sizes in ways that are related to age and sex, two known factors of beauty. These results provide further evidence to support the idea that makeup functions in part by modifying biologically based factors of beauty.

In conclusion, we have shown here that makeup changes the apparent size of the features. In two different, carefully controlled sets of photographs, the same women were photographed with makeup and without makeup. The eyebrows and eyes appeared larger with makeup than without makeup. Interestingly the noses appeared smaller with makeup, but only when a professional makeup artist applied the makeup. Finally, the mouth did not appear different in size with or without makeup. However, in high or low pass filtered images (including only fine details or only coarse features), the mouth did appear slightly larger. These findings are consistent with the idea that changing the apparent sizes of the features is one of the ways that makeup is able to enhance facial attractiveness. As feature size is related to age and sex, these findings provide further support to the notion that makeup functions in part by modifying biologically-based factors of beauty (Russell, 2010).

https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1087&context=psyfac

Abstract

Objective

Facial attractiveness has been reported to be influenced by visual features such as facial shape and the colour and texture of the skin. However, no empirical studies have examined the effects of facial skin radiance on facial attractiveness. The present study investigated whether types of skin reflection (i.e. radiant, oily and shiny, and matte) and the position of the reflection on the face influence facial attractiveness and other affective impressions.

Methods

A total of 160 female participants (1) estimated the ages and (2) evaluated attractiveness and other impressions of unfamiliar female faces in a total of seven skin reflection conditions. These conditions incorporated three types of reflection (i.e. radiant, oily and shiny, and matte) and three positions of the reflection on the face (i.e. entire facial skin, only cheeks, and only T-zone).

Results

The facial images of radiance on entire faces were rated as appearing younger than the facial images of oily shine on entire faces and the matte faces. Attractiveness ratings and other positive impressions increased in the order of the matte (ranked lowest), the oily shine on entire face, and the radiance on entire face (ranked highest) conditions. The reflection position also influenced facial attractiveness: attractiveness ratings and other positive impressions were higher in the radiance on entire face condition than in the radiant cheeks and the radiant T-zone conditions. Interestingly, the radiant cheek faces were rated more radiant and healthier but less feminine and less bright than the radiant T-zone faces.

Conclusion

These results suggest that facial radiance enhances facial attractiveness and conveys a wide variety of positive impressions on the observer. The magnitude of the effects of cheek radiance and T-zone radiance differs across various affective impressions. Nevertheless, the results demonstrate that cheek and the T-zone radiance both contribute to higher attractiveness and other positive impressions of the radiance on entire faces. We believe that our findings can contribute as a guide to the enhancement of positive facial impressions by means of skin radiance, thereby leading to a better understanding of the value of skincare and base makeup.

Abstract Research has demonstrated a positive effect of makeup on facial attractiveness (Cash et al., 1989; Russell, 2003; Etcoff et al., 2011). Makeup has also been found to inluence social perceptions (Etcoff et al., 2011; Klatt et al., 2016). While researchers have typically compared faces with makeup to faces without makeup, we propose that perceived effects will differ based on the amount of makeup that is applied. To test the effects of varying levels of makeup on perceived facial attractiveness, competence, and sociosexuality, participants assessed 35 faces with no makeup, light makeup, and heavy makeup; makeup was self-applied by participants, not applied by a makeup artist or the experimenter. Participants rated faces with makeup (either light or heavy) as more competent than those without makeup. In addition, participants rated faces with heavy makeup as significantly higher in attractiveness and sociosexuality than faces with light makeup. These results differ from previous research findings that faces with light makeup (applied by professional makeup artists) are perceived as most attractive. Our results suggest that when makeup is self-applied, faces with heavy makeup are perceived as more attractive and sociosexual than faces with light makeup, and faces with any level of makeup are rated as more competent.

Summary of Findings

In our investigation of makeup’s influence on perceived facial attractiveness, competence, and sociosexuality, we found that, as predicted, makeup had a significant effect on ratings for all three measures. Additionally, we found that no makeup, light makeup, and heavy makeup application significantly differed in their effects on perceived facial attractiveness, and sociosexuality. For competence judgments, we found that both the light and heavy makeup applications differed from the no makeup condition, but light and heavy makeup application did not differ from each other.

Conclusion

We found support for our proposal that makeup would have significant effects on perceptions of facial attractiveness, competence, and sociosexuality. Ratings of facial attractiveness and sociosexuality were highest for faces with heavy makeup. Ratings of competence for faces with light makeup and heavy makeup were both higher than ratings for faces with no makeup, but there were no differences between faces with light makeup and heavy makeup. Our results suggest that self-applied heavy makeup will provide more positive results for attractiveness judgments compared to self-applied light makeup, a finding that is counter to the advice often given in popular media. It is usually suggested that “less is more” and that lighter makeup is more attractive (Doyle, 2019; Almanza and Young, 2020). Our data show that people preferred the look of a heavier makeup application, at least in the conditions we tested. In contrast, the heavier makeup also led to perceptions of greater sociosexuality, but did not increase perceptions of competence. Research showing greater potential for harassment for those rated as having higher sociosexuality (Kennair and Bendixen, 2012) suggest that wearing heavy makeup may also have negative consequences. Thus, this study presents a more complex picture of makeup use for women, in which the amount of makeup a woman chooses to wear affects a variety of visual and social perceptions.

Implications ; the bad, and the very ugly

may the best (looking) man win: the unconscious role of attractiveness in employment decisions © 2013 Cornell HR Review

A recent New York Times article entitled “Up the Career Ladder, Lipstick in Hand” examined the effects of cosmetics on perceptions of women, with an eye toward wrangling any identified benefits for professional gain. 35 By gauging participants’ reactions to images of women with increasing quantities of makeup, the study concluded that makeup can not only enhance women’s attractiveness but also increase their perceived “likeability,” “competence,” and “trustworthiness.”36 Interestingly, the benefits held true past the point of “professional” makeup and into the “glamorous” aesthetic.37 These results indicate that like biological determinants of attractiveness, the performed elements of attractiveness can affect an individual’s experience and status. More importantly, they suggest the status and privilege associated with beauty may be attained through individual effort, in addition to biological good fortune.

Having discussed the biological aspects of female facial appeal, we see that makeup application tends to mimic our biological predilections: foundation satisfies the preference for smooth, homogenous skin;38 concealer camouflages blueish tones that detract from facial attractiveness;39 blush increases skin saturation, which is perceived as “attractive and healthy”;40 and lipstick creates the desired luminance contrast between skin and lip color.41 Not even the structural elements of facial attractiveness are beyond the reach of skillful makeup application, as glamour magazines regularly offer tutorials on applying makeup to create the illusion of wider eyes,42 fuller lips,43 and higher cheekbones.44 It is, therefore, unsurprising to discover that women are considered more attractive when wearing makeup. 45

In addition to using cosmetics, women can also influence their perceived attractiveness by manipulating their hair length, style, or color. A 2004 study found that long and medium-length hair worn down significantly improves a woman’s physical attractiveness, regardless how attractive she was initially rated with her hair pulled back . 46 In fact, women who were initially rated less attractive experienced nearly twice the improvement in ratings as their more attractive counterparts just by wearing longer hair. 47 Participants in another study rated blonde women not only more attractive than brunettes but also “more feminine, emotional, and pleasure seeking.”48 Clothing choices, too, play a role in determining attractiveness.

Researchers in one study attempted to identify the social cues communicated by various types of women’s dress.49 They photographed subjects in five different outfits (formal skirt, formal pants, casual skirt, casual pants, and jeans) and gauged participants’ reactions to the subjects in each form of attire.50 The results indicated that both males and females consider a woman wearing a formal skirt outfit most “happy, successful, feminine, interesting, attractive, intelligent, and wanted as a friend.”51 Conversely, subjects wearing jeans were rated lowest among each category. 52 These results demonstrate once again that women can not only influence their attractiveness, but can also elicit other desirable inferences generally bestowed upon attractive people simply by manipulating their appearance.

Abstract

It is now obvious that makeup increases perceived women’s attractiveness by men and women. Nevertheless, when it comes to the hiring process, the impact of the picture used on the curriculum vitae (CV) is often neglected. Our study aims to determine the circumstances under which corporal appearance can influence employers’ choices. We will analyze the moderating effects of facial aspects, especially the use of cosmetics as an embellishing agent. The results of our study, which were obtained through multiple correspondence tests concerning ready-to-wear salesperson job offers, have served to evaluate the extent of this impact. While all things being equal, our results show that professional makeup positively affects recruiter’s perception, and considerably increases the number of convocations for interview in France and Italy.

Results and discussion

First, we will analyse the results from all countries, and then we will group the results by country. Furthermore, we are considering that a positive response equals an invitation for a future job interview. The convocation is obtained either by e-mail or phone call. All the responses in Italy and France were obtained by phone calls. Out of 400 submitted applications, we received 149 positive replies. Previous studies discuss individuals’ preferences for embellished faces; applicants wearing makeup collect significantly more positive inferences.

Our literature review also examined the quantity and techniques of applying makeup. It appears that makeup needs to be applied professionally in order for it to be “effective” (Etcoff et al., 2011; Bielfeldt et al., 2013).

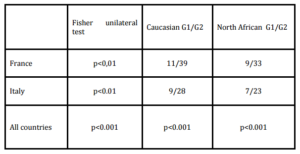

Table 1: Numbers of positive responses by countries and applicants – contingency table

The differences are statistically significant. This table shows us that makeup is related to the response variable. In other words, if G2 candidates get more positive responses, it is because makeup has a positive effect towards the person recruiting. Recruiters will tend to call back more embellished candidates (p<0.01 in France and Italy). It invalidates the hypothesis (H0) that the two variables are independent. Indeed, makeup impacts the responses to our candidates whether they are Caucasian or North African and either in France (p <0.01) or Italy (p <0.1). We also translated our results into the odds ratio in order to measure additional chances of getting a job interview.

Table 2: Odds ratio table

The odds ratio is frequently used in medicine, especially for risk calculation in developing cancer for smokers. However, we can also use the odds ratio in order to calculate the additional chances of belonging or developing something. Here, the odds ratio shows us that for glamorized candidates, there are significantly more positive chances of getting a positive response.

In France, getting a positive response is 11.55 times more likely with the use of cosmetics for saleswoman jobs in the ready-to-wear division. In Italy, these odds are 7.89 times higher. Without being too specific, the chances of getting a positive response to our two G2 candidates are at least 7 times greater when wearing professional makeup.

Conclusion

All things being equal, we emphasize the influence of professional makeup during the time of selection based on CV. For saleswoman jobs in the ready-to-wear division, the use of makeup allows our applicants to get at least 3 times more positive responses (Table 1). We also discussed this impact, depending on the types of candidates and countries. It appears that this impact is almost identical in France and Italy. The odds of getting a positive response from our G2 candidates are at least 7 times greater with professional makeup. The results obtained with the odds ratio are very significant (Table 2).

If it is easy to make a distinction between “without makeup, natural, professional and glamorous makeup” (Etcoff et al., 2011), a future research should draw the lines between these different uses of cosmetic products.

Regarding the methodology and in order to improve the validity of our results, a larger study could have been set up. First, the sample can be extended to a larger number of candidates and secondly the number of sent CVs could have been more consistent in order to strengthen our statistical processing. In addition, we could analyse the moderating effect of professional makeup thanks to the variance test (Evrard et al., 2003) to refine our analysis. Also, the mediation test would have determined whether the nature of the mediator makeup was the result of the enhancement of physical attractiveness or the activation of the stereotype “what has been cared for is good” (Graham and Jouhar, 1981). After all, it all comes down to knowing whether the recruiter, looking at a professionally embellished candidate, sees a “smart, honest and faithful” woman, or a beautiful and attractive woman.

Abstract The current study aimed to investigate the influence of facial cosmetics on perceptions of female applicants. In all, 286 participants were asked to evaluate the resume of a photographed female based on capability, earning potential, popularity, and hire-ability for either a “sales assistant” or “sales manager” role. It was hypothesized that perceived attractiveness and use of professional facial cosmetics would increase all ratings of professional competence. Further, facial cosmetics would be more advantageous for less attractive applicants and managerial applicants. The results supported these hypotheses, demonstrating that the use of professional facial cosmetics improved ratings of competence for female applicants. However, this enhancement was greater for less attractive female applicants and managerial applicants. Implications and limitations are discussed.

1.2. The Role of Facial Cosmetics in Selection Research in this area often fails to consider the extended phenotype of beauty: the use of facial cosmetics. These cosmetics are highly prevalent throughout the workplace, as 64% of surveyed females claimed to “always” wear makeup in to work, and nearly all of these women (98%) would wear makeup when attending a job interview (Leslie, 2013). Numerous studies demonstrate that perception of attractiveness can be directly enhanced through the application of facial cosmetics (Cash, Dawson, Davis, Bowen, & Galumbeck, 1989; Mulhern, Fieldman, Hussey, Leveque, & Pineau, 2003), particularly for less attractive women, as rated by observers (Jones & Kramer, 2016).

Following this line of logic, the current research aims to explore whether the use of facial cosmetics can interact with attractiveness to influence how women are perceived throughout the recruitment process. The existing literature demonstrates a significant effect of facial cosmetics on professional evaluations of women (Kyle & Mahler, 1996; Nash et al., 2006). Graham and Jouhar (1981) presented the earliest finding of an advantageous facial cosmetics bias in an organizational setting. Participants evaluated women wearing facial cosmetics to be more sociable, interesting, confident, poised, organized and popular. Mack and Rainey (1990) extended these positive effects of grooming (clothing, hair and facial cosmetics) to a recruitment setting. Wellgroomed applicants (wearing facial cosmetics) were deemed more hireable. Nash et al., (2006) found that both male and female participants judged women to be healthier and more confident when wearing facial cosmetics, and have more prestigious jobs with a greater earning potential.

The use of facial cosmetics has also been shown to dramatically increase appraisals for high social and professional status applicants as compared to low status applicants. These findings suggest that the effect of facial cosmetics may be stronger within women of high professional social status. However, it has also been suggested that female applicants wearing facial cosmetics are judged more harshly for both female-typed secretarial positions (Cox & Glick, 1986) and non-gender typed account positions (Kyle & Mahler, 1996). Kyle and Mahler (1996) revealed that the negative bias towards applicants K. Tommerup, A. Furnham DOI: 10.4236/psych.2019.104032 484 Psychology with facial cosmetics only presented itself within low status roles, for both female and male gender-typed roles. These findings support the notion that the use of facial cosmetics is related to social professional status as opposed to gender-typing of professions (Chao & Schor, 1998). Etcoff et al. (2011) found facial cosmetics had a significantly positive effect on likeability, competence and trustworthiness within automatic judgements.

4. Discussion In the current study it was hypothesized that higher levels of attractiveness and professional use of facial cosmetics would increase ratings of capability, earning potential, popularity, and hire-ability for female applicants under a resume evaluation procedure. Secondly, facial cosmetics would be more advantageous for less attractive applicants and managerial applicants. The first three hypotheses were fully supported, while the final hypothesis received partial support through statistical analysis. The current findings conclude that perceptions of women in recruitment procedures are significantly increased by use of facial cosmetics. However, contrary to previous findings, the extent of this facial cosmetics bias depends upon level of perceived attractiveness and professional status.

Abstract

During the COVID-19 pandemic, wearing facemasks was mandatory in the United Kingdom except for individuals with medical exemptions. Facemasks cover the full lower half of the face; however, the effect of facemasks on age perception is not yet known. The present study examined whether age estimation accuracy of unfamiliar young adult women is impaired when the target is wearing a facemask. This study also examined whether makeup, which has previously been shown to increase error bias, further impairs age estimation accuracy when paired with a facemask. The findings indicate that both facemasks and makeup tend to result in overestimation of the young women's age compared to neutral faces, but the combination of both is not additive. Individual level analysis also revealed large individual differences in age estimation accuracy ranging from estimates within 1 year of the target's actual age, and age estimates which deviated by up to 20 years.

1 INTRODUCTION

Accurate age estimation of strangers is paramount in situations relating to forensic age identification in criminal investigations (Thorley, 2018) and age verification for age restricted sales (Willner & Rowe, 2001). Laboratory studies demonstrate that age estimates are moderately accurate with errors within the range of 3–5 years in adults (Sörqvist & Eriksson, 2007). However, factors which impair age estimation accuracy by up to 8 years have also been identified (Clifford et al., 2018; Dehon & Brédart, 2001; Voelkle et al., 2012; for reviews see Moyse, 2014; Rhodes, 2009). One example is the use of sunglasses to obscure the eye region and disguise visual cues of age within this region (Thorley, 2021). However, the effect of obscuring other facial features on age perception is less known.

During the COVID-19 pandemic in the UK, individuals were mandated to wear a facemask when indoors with members of different households or with strangers, when on public transport, in shopping centres and supermarkets, and on hospitality premises (Department of Health and Social Care, 2020). Although use of facemasks potentially presents a challenge for salespeople selling alcohol, knives or other age-restricted items, the effect of facemasks on age estimation accuracy is not known. The challenge is further compounded by individuals who may unintentionally or deliberately attempt to appear older when wearing a facemask by also applying facial cosmetics to alter the visual cues of the visible facial features. Stores are encouraged to use the ‘Challenge 25’ Policy and should therefore request identification to confirm that the buyers are over the age of 18 when they perceive an individual to be under the age of 25. However, the extent to which facemasks can impair age estimation accuracy, if at all, is not clear. Although government mandates to wear facemasks will gradually lift as the pandemic subsides, some people will choose to continue to wear facemasks as evident from some cultures during pre-pandemic times (Lau et al., 2010). Therefore, the question of whether facemasks, and makeup, distort age perception will likely continue to be relevant even after restrictions have been lifted.

The perceived age of women is typically found to be less accurate compared to men (Voelkle et al., 2012), with younger faces frequently overestimated and older faces underestimated (Voelkle et al., 2012; Watson et al., 2016). The discrepancy between men and women may be attributed, at least in part, to the use of cosmetics. Women are more likely than men to apply cosmetics to alter their physical appearance usually with the desired effect of appearing more attractive and decreasing negative self-perception (Korichi & Pelle-de-Queral, 2008). Previous studies revealed that faces wearing cosmetics are judged as healthier (Nash et al., 2006) and more attractive (Mulhern et al., 2003), and the latter correlates negatively with perceived age (Henss, 1991). Although the effect of cosmetics on human age estimation has not been extensively researched, a small set of studies support the notion that cosmetics alter the perception of age (Russell, 2003; Russell et al., 2019).

Cosmetics alter the perception of specific facial features, which act as visual cues for age. One cue is facial contrast, which comprises the colour differences and luminance in the skin and between the facial features. Facial contrast changes with age, and faces with increased facial contrast (e.g. darker eyebrows and lips) are perceived to be younger compared to those with decreased facial contrast (Porcheron et al., 2013). Consequently, makeup, which is applied to darken the lips, increase skin luminance, and increase the colour contrast of the eyes and eyebrows, work to increase facial contrast and result in younger looking faces (Russell et al., 2019). Makeup applied to different facial features also has different effects on age perception. For example, makeup applied to the eyes and eyebrows has a stronger impact on age perception compared to application to the lips (Russell et al., 2019). Additionally, the effects of these manipulations to the appearance of the face are dependent on the target age (Egan & Cordan, 2009; Russell et al., 2019). Specifically, photographs of faces depicting 40 and 50-year-old women are perceived on average 1.5 years younger when wearing full makeup, while 20-year-old women appear 1.4 years older with identical makeup (Russell et al., 2019). Although these estimation errors are relatively modest, other studies have reported a larger range of errors of up to 20 years older or younger than actual age (Dayan et al., 2015; Fink et al., 2006).

The difference in the strength of the effects when applying makeup to lips compared to the eye region suggests that some facial features may play a more prominent role in providing visual cues to age. Only a small set of studies have examined the effect of obscuring different facial features on age perception. In those studies, obscuring head shape and hair did not decrease accuracy (George & Hole, 1995), but obscuring the eye region led to a greater reduction in accuracy compared to disguising the hair and forehead or no disguise at all (Thorley, 2021). Furthermore, a recent eye-tracking study suggests that the central triangle (collectively eyes, nose, and mouth) may be important for age estimation (Liao et al., 2020). It is therefore not inconceivable that obscuring any visual information within the central triangle would disrupt the age estimation process. However, these studies did not specifically obscure the lower half of the face, and therefore the impact of wearing a facemask on age perception is not yet known.

Furthermore, individuals may also apply makeup, which, in addition to the facemask, could decrease age estimation accuracy further. The combined effect of makeup and masks on age perception is yet to be examined. As makeup to the eyeregion has been found to introduce more errors compared to other regions (Russell et al., 2019), makeup application to the eyes in combination with an absence of visible visual cues from the entire bottom half of the face, could result in further deterioration of age estimation accuracy. Our aim was to determine whether wearing a facemask or makeup affects age estimation accuracy, and whether pairing facemasks and makeup would further increase age estimation error. Specifically, we expected that makeup would increase the perception of age for young adult women, and that facemasks would impair age estimation; however, we did not predict whether the impairment would be biased towards an over or underestimation of age. Furthermore, we expected that the combined use of facemasks and makeup would yield a greater increase in overestimation bias compared to makeup alone, due to a reduction in facial age cues and enhancing of visible cues (eye region) through cosmetics.

4 DISCUSSION

This is the first study to investigate the effect of facemasks, and the combined effect of wearing a facemask with makeup, on the perception of age of young adult female faces. Faces across all four conditions were perceived as older than their actual age. Overestimation was greater for faces wearing a facemask or wearing makeup, but contrary to our prediction, a combination of both did not impair performance further. The findings also revealed a large range of individual differences in age estimation ability across all conditions.

In line with previous findings, 18- to 21-year-olds were perceived to be older than their actual age by at least 1 year (Thorley, 2021; Willner & Rowe, 2001) and this upward bias increased with the application of makeup (Russell et al., 2019). The reason for this upward bias effect of makeup on young faces is not fully understood, and contrasts with the more youthful appearance of older people wearing makeup (Russell et al., 2019). Although older faces appear more youthful because of feature size manipulation (e.g. making eyes appear larger), increasing feature contrast, and enhancing skin homogeneity (Russell et al., 2019), enhancing these features in younger women does not reduce their perceived age. Rather, it has been suggested that makeup in younger women acts as a visual contextual cue activating judgements influenced by beliefs about social norms, specifically that makeup use is associated with adulthood (Russell et al., 2019).

In the present study, we also examined the effect of facemasks on age estimation accuracy. Masked faces were estimated to be approximately 4 years older than their actual age compared to 2 years older when unmasked. We note that the average error of 4 years falls within the range of error found in some other studies (e.g. Clifford et al., 2018; Dehon & Brédart, 2001; Sörqvist & Eriksson, 2007), and by comparison the effect of facemasks on age estimation may not appear large. However, these studies differ methodologically (for example, use of time pressure versus self-paced, accessories on face and hair, average age of perceivers) and consequently the tasks also differ in difficulty. Therefore, such direct comparisons of error across studies offer limited insight.

Although previous research suggests that the eye region is an important facial feature for accurate age judgements (Jones & Smith, 1984), disrupting the processing of other facial features while keeping the eye region intact also impaired age estimation accuracy in this study. However, this raises the question of whether the pattern found here is driven by an individual facial feature obscured by the mask, a combination of features, or the disruption of the central triangle of the face. Few studies have examined the role of individual features in age perception (Jones & Smith, 1984; Liao et al., 2020). Of these, it was found that children aged 3–9 made more errors during the ranking of adult faces by age when the eye region was masked, compared to when the faces were unmasked, or when a combination of features were masked (mouth and chin, or face shape) (Jones & Smith, 1984). The masked nose and cheek condition also produced more errors than the other conditions, though not to the same extent as the masked eye region. In a recent eye-tracking study, observers directed their gaze towards the central triangle of the face both when viewing adult faces freely and when tasked to estimate ages, however in the tasked condition, eye gaze was also redirected towards the lower part of the face (Liao et al., 2020). Both these studies suggest that the bottom half of the face is important for age estimation, and our findings add further support. The present study is a first step for demonstrating the impact of facemasks on age perception; however, the theoretical mechanism underlying this effect is beyond the scope of this paper and a systematic examination of different facial features on age perception is an important avenue for further investigation.

We also examined the combined effect of makeup and facemasks. Results indicate that wearing makeup or a facemask individually increased the upward bias by an average of 1.2 and 1.7 years, respectively. However, estimation bias did not increase further when facemasks and makeup were combined. This finding is contrary to our prediction that wearing a facemask and applying makeup would increase error bias even further given the pertinent role of makeup to the eyeregion compared to other facial features (Russell et al., 2019). To increase ecological validity, the style and intensity of makeup was left to participants to apply in a manner that was natural for them to wear to a formal event. For this reason, we did not control for the intensity of makeup applied to faces. Although research has not found a difference in age estimation bias when using different makeup intensities (Russell et al., 2019), it is plausible that makeup intensity to the eye region, when paired with a facemask, could influence age estimation differently due to a reduction on reliance from other visual cues for age judgements.

This study also explored age estimation ability at an individual level. Findings demonstrate that there is a broad range in ability, while some individuals were fairly accurate in their estimates (within = ±1 year), others provided estimates with a deviation of up to 20 years over the target's actual age. Furthermore, older observers overestimated faces to a greater degree when the faces were wearing a mask, makeup, or both, but this pattern did not reach significance when the face was without makeup or mask. These findings support previous research suggesting that the perceiver's age influences age estimation from faces in two ways. First, studies have reported a general decline in age estimation accuracy linked to cognitive ability for older participants compared to younger participants (Voelkle et al., 2012). Secondly, an own-age bias has also been previously recorded, demonstrating an advantage for estimating ages of faces similar to that of the observer (Moyse et al. (2014); Willner & Rowe, 2001) but this pattern is not consistent across studies (Burt & Perrett, 1995). Further exploratory analysis for perceiver age bias in the present study is provided in the supplementary materials, this analysis indicates that perceivers over the age of 34 produced greater error in their estimates of 4.4 years compared to 1.8 years by perceivers under the age of 34 across all conditions. As this study did not set out to investigate own-age bias and therefore did not include the older target faces for a comparison group, it is not possible to conclude whether perceiver age bias found here is due to age related decline or an effect of own-age bias.

Other group characteristics may also account for some of the variance recorded in the present study, namely gender and ethnicity of stimulus and participants. Although these characteristics have not been extensively documented, existing findings suggest that Caucasian participants perform better when evaluating Caucasian faces (Dehon & Brédart, 2001; Thorley, 2021), but this own-ethnicity bias does not persist for African participants (Dehon & Brédart, 2001). Few studies have examined own-gender bias in age estimation from faces, and those which have did not find evidence to support this (Dehon & Brédart, 2001; Voelkle et al., 2012). The present study did not examine gender and ethnicity bias, however this may warrant further investigation.

Despite these findings, there are some limitations to consider. Only female faces were used to examine the interaction of makeup and facemasks. Some studies report an advantage for accuracy of male faces compared to female faces (Dehon & Brédart, 2001; Voelkle et al., 2012) which may be due to women being more likely to apply cosmetics and makeup to their faces (87% of women compared to 7% of men reported wearing makeup at least once in a government survey; Waldersee, 2019). It is therefore not known whether facemasks and makeup affect the perceived age of men and women differently. Additionally, to control for extraneous variables we did not include the rest of the body in this experiment. While faces have been found to provide the strongest cue for age leading to least errors (Cattaneo et al., 2009), additional visual cues from the body, such as body height and shape, could be used by the assessor to provide a more accurate estimate.

Finally, this study focussed on young women aged 18–21, although it is not inconceivable to expect similar patterns with 17-year-old women considering the ages of 13- and 16-year-old girls also tend to be overestimated under ‘normal’ conditions (Willner & Rowe, 2001). However, face age estimation research with adolescence remains scarce and further work examining the effect of facemasks and makeup with adolescent faces is warranted. Nonetheless, the findings with the 18- to 21-year age group are relevant still. Although the most common minimum purchasing age in the European region is 18 years old, minimum age restrictions vary widely across countries and in some cases also depend on the item of sale (for example, beverage type for alcohol sales). Specifically, for example, in Norway and Sweden, the age limit for beer and wine is 18, but rises to 20 for sales of spirits (Kadiri, 2014), and in some states of the United States of America, Sri Lanka, and Egypt, the law restricts sale of alcohol to individuals aged 21 and over (International Alliance for Responsible Drinking [IARD], 2020).

In conclusion, these findings offer some practical implications, particularly in the context of age estimation in the sales of restricted items. Although the ‘Challenge 25’ policy is in place in the United Kingdom to encourage sales personnel to verify identification for individuals appearing under the age of 25, many countries do not implement a similar retail sales strategy. Even with such a policy in place, the wide range in estimation ability with some individuals (specifically, 12% on average for neutral faces and between 13% and 20% on average for faces wearing a makeup, a facemask, or both) who overestimated age by 7 or more years, suggests that a percentage of young women may still be incorrectly perceived to be older than 25. The ‘Challenge 25’ policy therefore goes some way to mitigate risk of sales to minors but does not eliminate the potential for decisional errors among those whose age estimation skills are poor, and the potential for error increases further when faces are partially obscured or transformed with the application of makeup.

Finally, the range of individual ability found here also indicates broader implications extending to settings which require security personnel to make age judgements. For example, for the classification of children and adults of undocumented refugees by immigration officers or for the identification of minors in the assessment of online illicit content by internet safety officers. In such situations, it may be beneficial to delegate such tasks to groups of people who are proficient in the task, though, further work to understand individual differences is needed and we hope that these findings will prompt further research in this field.

Abstract

Human bodies are sometimes cognitively objectified, i.e., processed less configurally and more analytically, in a way that resembles how most objects are perceived. Whereas how people process images of sexualized bodies appearing in the mass media has been well documented; whether subtler manifestations of sexualization, such as wearing makeup, might elicit cognitive objectification of ordinary women’s faces, remains unclear. The present paper aims at filling this gap. We hypothesized that faces wearing makeup would be processed less configurally than faces wearing no makeup. Sixty participants took part in a face recognition task, in which faces wearing or not wearing makeup were presented. In regards to faces with no makeup, people recognized face parts better in the context of whole faces than in isolation, which served as evidence of configural processing. In regards to faces wearing makeup, face parts were recognized equally well when presented in isolation vs. in the context of whole faces; evidence of a lower configural processing. That pattern of results was driven by eye makeup (vs. lipstick). Implications for research on objectification and sexualization are discussed.

Why Would Women’s Faces Wearing Makeup Be Cognitively Objectified?

Cognitive objectification studies have been informative regarding how people visually process images of sexualized bodies that appear in the visual media, but they have remained silent regarding whether subtler manifestations of sexualization, such as the use of heavy makeup, might affect the way people see women. Sexualization may be communicated through bodily cues (Hatton & Trautner, 2011), but also through facial ones (e.g., puckering lips: Messineo, 2008). Research on sexualization mostly focused on body sexualization (e.g., Bernard et al., 2019) and it thus remains unclear whether face sexualization might affect the way people visually process women’s faces.

The present study hypothesized that face sexualization might diminish configural face processing. In line with this hypothesis, Tanaka (2016) found that faces with lipstick were associated with larger N170s than faces without makeup (but eye shadow did not modulate the N170s), suggesting that cosmetics induce subtle alterations in face processing. However, this study relied only on faces for which configural face information remained intact (i.e., not altered through e.g., inversion or scrambling). Whether faces with makeup are processed less configurally than faces without makeup remains therefore an open question. We hypothesized that faces with makeup would be processed less configurally than faces with no makeup. We relied on a whole/parts paradigm in which face parts were presented either in isolation or in a whole face context. Concerning faces without makeup, we expected that recognition performance would be improved when face parts are presented in a whole face context vs. in isolation, evidencing configural processing. Concerning faces wearing makeup, we predicted that face parts would be recognized equally well when presented in isolation vs. in a whole face context, evidencing lower face configural processing. We also examined whether the effect of face sexualization on face processing was moderated by the location of makeup (eyes vs. mouth).

Finally, we also explored and reported the reaction times associated with recognition performance. Reaction times are indeed important to consider for two reasons. Reaction times are informative regarding whether participants properly followed instructions i.e., performing the recognition task as fast as possible. Moreover, reaction times also enable us to test whether a speed-accuracy bias is at play, i.e., whether the interaction between target face sexualization and the recognition task might be driven by more time spent at looking at face parts vs. whole faces wearing makeup vs. no makeup.

In sum, our results suggest that faces with no makeup were recognized configurally with a better recognition of face parts when presented in the context of whole faces than when presented in isolation. In contrast, for faces with makeup, faces parts were recognized equally well regardless of whether they were presented in the context of whole faces or in isolation, evidencing lower configural processing, and this pattern was driven by eye makeup specifically.

Discussion

Most research on objectification and sexualization has documented how body sexualization triggers cognitive objectification and related dehumanization (for reviews, see Bernard, Gervais et al., 2018; Ward, 2016), showing that sexualized bodies are less likely to be processed as wholes and more likely to be processed in an analytic, part-based manner, in a way that resembles how most objects are typically processed. In line with the tenets of Objectification Theory (Fredrickson & Roberts, 1997), this recent line of research provided converging evidence that people tend to cognitively reduce sexualized bodies to their body parts (e.g., Bernard, Rizzo et al., 2018; Bernard et al., 2019). However, very little was known about whether subtler manifestations of sexualization, such as the use of makeup, might affect the way we see ‘ordinary’ women. To fill this gap, we examined whether sexualized faces with makeup, akin to sexualized bodies, were reduced to their parts.

Consistent with the notion that sexualization can be conveyed through facial cues (Messineo, 2008; Smolak et al., 2014), we found that faces with makeup were perceived as being more sexualized than faces without makeup. However, it is worth noting that faces with makeup were rated as moderately sexualized, which indicates that perceived sexualization based on facial cues is subtler than perceived sexualization associated with posture suggestiveness and nudity (e.g., Bernard et al., 2019).

Contrary to our hypothesis, the interaction between face sexualization and recognition task was not significant. However, our results revealed an interaction between face sexualization, recognition task and face parts. The examination of simple effects revealed that faces with makeup were processed less configurally than faces without makeup and this pattern was specifically driven by eye makeup, not by lipstick. Mouths with lipstick were better recognized in the context of whole faces. In contrast, we found that eyes with makeup were equally well recognized in isolation than in the context of whole faces, indicating that eye makeup caused a specific analytic processing of these face parts. The absence of interaction between recognition task and makeup when considering reaction times suggests that the differences found in the recognition performance for faces with makeup vs. without makeup were not driven by a speed-accuracy bias (e.g., longer reaction times associated with the recognition of face parts for faces with makeup vs. no makeup).

Whereas previous research showed that focusing on people’s faces might temper the effects of appearance-focus and sexualization on cognitive objectification (Bernard, Gervais, Holland, & Dodd, 2018; Gervais, Holland, & Dodd, 2013; Nummenmaa, Hietanen, Santtila & Hyönä, 2012) and related dehumanization (Gray et al., 2011; Loughan et al., 2010), our results suggest that such intervention may not be efficient when faces are sexualized, especially through the use of eye makeup (e.g., mascara).

Presenting no-makeup selfies interspersed with idealized made-up images may be beneficial for women’s body image. However, the impact of viewing only no-makeup selfies is still unknown, as is the influence of any positive appearance-related comments from others accompanying those images on social media. Thus, in the present study, we examined the impact of viewing either: (1) idealized images with appearance-related comments, (2) idealized images with appearance-neutral comments, (3) no-makeup images with appearance-related comments, or (4) no-makeup images with appearance-neutral comments, on young women’s (N = 394) appearance satisfaction, mood, appearance comparison frequency, and perceived attainability. Viewing idealized selfies of attractive women reduced women’s satisfaction with their overall and facial appearance. Viewing natural no-makeup images of those attractive women also reduced women’s facial satisfaction but had no impact on overall appearance satisfaction. No-makeup selfies resulted in less frequent appearance comparisons and higher perceived attainability than idealized images. There was no impact of appearance-related comments on any of the outcomes. The results suggest that no-makeup images are less detrimental to young women’s body image than idealized images.

Makeup is known to increase female facial attractiveness, but it is unclear how. To investigate how makeup enhances beauty, we took a theoretically driven approach, borrowing from the rich literature on facial attractiveness and testing the proposal that cosmetics increase attractiveness by modifying 5 known visual factors of attractiveness: symmetry, averageness, femininity (sexual dimorphism), age, and perceived health. In 6 studies using 152 carefully controlled images of female faces with and without makeup, participants rated the faces on attractiveness and on each of the 5 factors. We analyzed the effect of makeup on these factors and analyzed whether the factors mediated the effect of makeup on attractiveness. Makeup affected all the factors. Averageness, femininity, and health individually mediated the effect of makeup on attractiveness. Finally, with all five factors as mediators in a multiple mediation model, we observed full mediation of the effect of makeup on attractiveness, almost entirely via femininity and health. These findings support a scientific understanding of how makeup works based on the manipulation of visual factors of facial beauty.

Factors of Beauty

Evidence has emerged for several biologically based visual factors of attractiveness, including preferences for bilateral symmetry, averageness (i.e., proximity to the average of the faces of a given population), sexual dimorphism (e.g., femininity for female faces), youth, and health. We describe each of these five factors in turn, describing the evidence that each factor plays a role in the perception of attractiveness, and noting reasons to believe that makeup could affect the factor. There is at least some evidence that femininity, age, and health are affected by makeup, and that symmetry is not affected by makeup. The effect of makeup on the perception of averageness has not been tested.

Okay lets recap;

Why do women wear makeup?

Why do women wear makeup?

- To be viewers more competent, younger or maturer (depends on the individual circumstance).

- To hide their emotional state and reactions.

- Securing higher recruitment prospects and social occupational success.

- Increasing their perceived levels of facial attractiveness, halo, and sociosexuality.

- Using makeup as a tactic to attract mates and compete with rivals.

well i guess that all for now folks; enjoy this masterpiece

View: https://youtu.be/jhC1pI76Rqo

Attachments

Last edited: