T

tlightz

Recruit

★★

- Joined

- Nov 9, 2017

- Posts

- 152

‘Leftover men’. China’s single men are referred to as “shengnan” (剩男), ‘leftover men’- a new report has given a

profile of the general Chinese single male: lower class, lower education and low income.

On March 14th 2013, China biggest matchmaking website ‘Shiji Jiayuan’ published a report titled “Confessions of Leftover Men” about their nationwide research on the background of China’s single men, who are referred to as “shengnan” (剩男), ‘leftover men’. Their research involved an extensive online survey of 56.013 single men born between the 1970s and 1980s. Some of their findings: the rate of single men is highest in Guangxi with a 34.9% percentage; 49% of them do not own a house or car; 60% of them admit to being a so-called ‘zhainan’ (a ‘geek’ with low social interaction) (China Daily 2013, Sina 2013). This account of China’s single men poses a stark contrast to that of China’s unmarried woman, the ‘shengnü’ (剩女), who has been profiled as being successful, sexy and single. The new report on single men coins many questions: why is it so hard for these Chinese men to find women? What is the main reason for their unmarried status? And why is their general profile so different from their female ‘leftover’ counterparts?

In “Confessions of Leftover Men”, China’s shengnan give several reasons for their single existence. They simply do not know how to court a lady, they do not have the courage to approach a woman or are too busy with work (China Daily 2013). Luckily for them, they generally do not really start worrying about getting married until they reach the age of 34. The ladies have different reasons for not being married, such as a focus on their careers and independence, and the mere fact that they have not met the right person who can live up to their (high) expectations (Lake et al 2013)

Traditionally, Chinese women prefer “marrying-up” and look for a spouse who has a better educational background and who has a higher salary than they do. The men traditionally want to marry women who can admire them and are therefore a bit lower than they are in terms of education and salary.

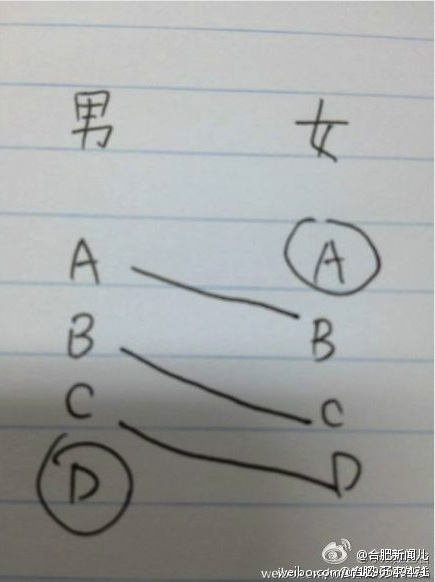

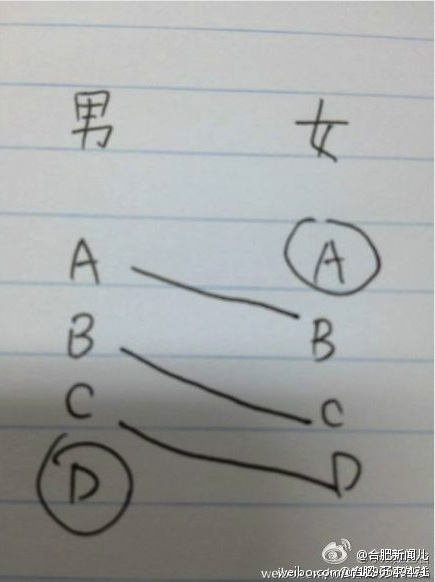

When we divide these men and women into A, B, C and D groups, the A-men would generally marry B-women and the B-men would wed a C-woman. Approaching the problem in this way, Zhang indicates that it will generally be the “A-women” and the “D-men” that get “left behind” (Sina 2013). This explains the big difference in ‘leftover women’ and ‘leftover men’: the first are often the educated, higher class, attractive girls, whilst the latter are mostly the poorer, lower class and less-educated men.

As Chen (2011) points out: “In China, marriage involves much more than a couple truly in love. The material base is given lots of consideration. Men and women act with market logic, considering their own needs and backgrounds when choosing spouses”: their marriage has become a market strategy instead of a romantic choice. The only way to break this cycle is for China to move away from dominant traditional expectations on marriage and bring marriage back to where it belongs: out of the market domain, and into the sphere of love.

Full article/source:

https://www.whatsonweibo.com/leftover-men-and-women/

profile of the general Chinese single male: lower class, lower education and low income.

On March 14th 2013, China biggest matchmaking website ‘Shiji Jiayuan’ published a report titled “Confessions of Leftover Men” about their nationwide research on the background of China’s single men, who are referred to as “shengnan” (剩男), ‘leftover men’. Their research involved an extensive online survey of 56.013 single men born between the 1970s and 1980s. Some of their findings: the rate of single men is highest in Guangxi with a 34.9% percentage; 49% of them do not own a house or car; 60% of them admit to being a so-called ‘zhainan’ (a ‘geek’ with low social interaction) (China Daily 2013, Sina 2013). This account of China’s single men poses a stark contrast to that of China’s unmarried woman, the ‘shengnü’ (剩女), who has been profiled as being successful, sexy and single. The new report on single men coins many questions: why is it so hard for these Chinese men to find women? What is the main reason for their unmarried status? And why is their general profile so different from their female ‘leftover’ counterparts?

In “Confessions of Leftover Men”, China’s shengnan give several reasons for their single existence. They simply do not know how to court a lady, they do not have the courage to approach a woman or are too busy with work (China Daily 2013). Luckily for them, they generally do not really start worrying about getting married until they reach the age of 34. The ladies have different reasons for not being married, such as a focus on their careers and independence, and the mere fact that they have not met the right person who can live up to their (high) expectations (Lake et al 2013)

Traditionally, Chinese women prefer “marrying-up” and look for a spouse who has a better educational background and who has a higher salary than they do. The men traditionally want to marry women who can admire them and are therefore a bit lower than they are in terms of education and salary.

When we divide these men and women into A, B, C and D groups, the A-men would generally marry B-women and the B-men would wed a C-woman. Approaching the problem in this way, Zhang indicates that it will generally be the “A-women” and the “D-men” that get “left behind” (Sina 2013). This explains the big difference in ‘leftover women’ and ‘leftover men’: the first are often the educated, higher class, attractive girls, whilst the latter are mostly the poorer, lower class and less-educated men.

As Chen (2011) points out: “In China, marriage involves much more than a couple truly in love. The material base is given lots of consideration. Men and women act with market logic, considering their own needs and backgrounds when choosing spouses”: their marriage has become a market strategy instead of a romantic choice. The only way to break this cycle is for China to move away from dominant traditional expectations on marriage and bring marriage back to where it belongs: out of the market domain, and into the sphere of love.

Full article/source:

https://www.whatsonweibo.com/leftover-men-and-women/