Intellau_Celistic

5'3 KHHV Mentalcel

-

- Joined

- Aug 26, 2021

- Posts

- 166,411

Novel Schizophrenia Risk Gene TCF4 Influences Verbal Learning and Memory Functioning in Schizophrenia Patients

Abstract. Background: Recently, a role of the transcription factor 4 (TCF4) gene in schizophrenia has been reported in a large genome-wide association study. It has been hypothesized that TCF4 affects normal brain development and TCF4 has been related to different forms of neurodevelopmental...karger.com

Common sequence variants have recently joined rare structural polymorphisms as genetic factors with strong evidence for association with schizophrenia. Here we extend our previous genome-wide association study and meta-analysis (totalling 7 946 cases and 19 036 controls) by examining an expanded set of variants using an enlarged follow-up sample (up to 10 260 cases and 23 500 controls). In addition to previously reported alleles in the major histocompatibility complex region, near neurogranin (NRGN) and in an intron of transcription factor 4 (TCF4), we find two novel variants showing genome-wide significant association: rs2312147[C], upstream of vaccinia-related kinase 2 (VRK2) [odds ratio (OR) = 1.09, P = 1.9 × 10−9] and rs4309482[A], between coiled-coiled domain containing 68 (CCDC68) and TCF4, about 400 kb from the previously described risk allele, but not accounted for by its association (OR = 1.09, P = 7.8 × 10−9).

Common SNPs in the transcription factor 4 (TCF4; ITF2, E2-2, SEF-2) gene, which encodes a basic Helix-Loop-Helix (bHLH) transcription factor, are associated with schizophrenia, conferring a small increase in risk. Other common SNPs in the gene are associated with the common eye disorder Fuch's corneal dystrophy, while rare, mostly de novo inactivating mutations cause Pitt-Hopkins syndrome. In this review, we present a systematic bioinformatics and literature review of the genomics, biological function and interactome of TCF4 in the context of schizophrenia. The TCF4 gene is present in all vertebrates, and although protein length varies, there is high conservation of primary sequence, including the DNA binding domain. Humans have a unique leucine-rich nuclear export signal. There are two main isoforms (A and B), as well as complex splicing generating many possible N-terminal amino acid sequences. TCF4 is highly expressed in the brain, where plays a role in neurodevelopment, interacting with class II bHLH transcription factors Math1, HASH1, and neuroD2. The Ca2+ sensor protein calmodulin interacts with the DNA binding domain of TCF4, inhibiting transcriptional activation. It is also the target of microRNAs, including mir137, which is implicated in schizophrenia. The schizophrenia-associated SNPs are in linkage disequilibrium with common variants within putative DNA regulatory elements, suggesting that regulation of expression may underlie association with schizophrenia. Combined gene co-expression analyses and curated protein–protein interaction data provide a network involving TCF4 and other putative schizophrenia susceptibility genes. These findings suggest new opportunities for understanding the molecular basis of schizophrenia and other mental disorders. © 2012 Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

Scientific progress in understanding human disease can be measured by the effectiveness of its treatment. Antipsychotic drugs have been proven to alleviate acute psychotic symptoms and prevent their recurrence in schizophrenia, but the outcomes of most patients historically have been suboptimal. However, a series of findings in studies of first-episode schizophrenia patients transformed the psychiatric field’s thinking about the pathophysiology, course, and potential for disease-modifying effects of treatment. These include the relationship between the duration of untreated psychotic symptoms and outcome; the superior responses of first-episode patients to antipsychotics compared with patients with chronic illness, and the reduction in brain gray matter volume over the course of the illness. Studies of the effectiveness of early detection and intervention models of care have provided encouraging but inconclusive results in limiting the morbidity and modifying the course of illness. Nevertheless, first-episode psychosis studies have established an evidentiary basis for considering a team-based, coordinated specialty approach as the standard of care for treating early psychosis, which has led to their global proliferation. In contrast, while clinical high-risk research has developed an evidence-based care model for decreasing the burden of attenuated symptoms, no treatment has been shown to reduce risk or prevent the transition to syndromal psychosis. Moreover, the current diagnostic criteria for clinical high risk lack adequate specificity for clinical application. What limits our ability to realize the potential of early detection and intervention models of care are the lack of sensitive and specific diagnostic criteria for pre-syndromal schizophrenia, validated biomarkers, and proven therapeutic strategies. Future research requires methodologically rigorous studies in large patient samples, across multiple sites, that ideally are guided by scientifically credible pathophysiological theories for which there is compelling evidence. These caveats notwithstanding, we can reasonably expect future studies to build on the research of the past four decades to advance our knowledge and enable this game-changing model of care to become a reality.

Scientific progress in understanding human disease can be measured by the effectiveness of its treatment. There are three ways in which it can be measured: alleviation of symptoms without affecting the disease course (e.g., l-dopa for Parkinson’s disease, cholinesterase inhibitors for Alzheimer’s disease, triptans for migraine headaches); prevention of progression, but not curative (e.g., glatiramer and interferon for multiple sclerosis, anticoagulants for cerebrovascular disease, anticonvulsants for seizure disorders); and curative or preventive (e.g., surgical procedures for tumors, antibiotics and vaccines for infectious diseases).

The first effective treatment for schizophrenia and related psychotic disorders was chlorpromazine, the prototypical antipsychotic drug (1). Numerous other compounds were subsequently developed, all of which work by a common mechanism of action: inhibition of dopamine at the postsynaptic D2 receptor. More than four decades of research with antipsychotics has definitively proven their efficacy in alleviating psychotic symptoms and preventing symptom recurrence (2–4). Despite these results, antipsychotics were considered to be a symptomatic treatment, acting like cholinesterase inhibitors for Alzheimer’s disease or l-dopa for Parkinson’s disease, and were not believed to resolve the fundamental pathology or alter the course of the illness (5, 6).

However, beginning in the late 1980s, studies of first-episode psychosis patients (7), in conjunction with seminal reviews by McGlashan (8) and Wyatt (9), revealed two revolutionary findings that challenged that premise: 1) longer durations of untreated psychosis were associated with worse treatment responses and outcomes (10, 11); and 2) a significant portion of first-episode psychosis patients could achieve symptom remission and recovery if they received effective treatment in a timely fashion (12–14). These studies indicated that the timing of treatment in first-episode patients was a critical factor in determining their prognoses. More generally, they also suggested that active psychosis was, in effect, “bad for the brain” in that it reflected an underlying pathophysiologic process that was progressive unless alleviated by treatment.

These findings significantly influenced scientific thinking and clinical approaches to schizophrenia and raised the possibility of treatment being able to limit its morbidity and even prevent its onset—or, in other words, modify the course of the illness. In this article, we review the evidence for this radical reconceptualization of schizophrenia and therapeutic prospects for those affected.

Nosology: the Early Classification of Schizophrenia

Progress in understanding schizophrenia can be said to begin with the description of dementia praecox by Pick and Kraepelin (15, 16) (Table 1). (Before that, psychiatric nosology was chaotic and characterized by a conflicting mosaic of inconsistent systems in which disease categories were based on short-term and cross-sectional observations of patients, from which the putative characteristic signs and symptoms of a given disease concept were derived.) The dominant psychiatric constructs, which gave a semblance of order to this fragmentary nosology, were the theory of degeneration and the concept of “unitary psychosis” (Einheitspsychose) (17). What distinguished what we now call schizophrenia from other conditions whose clinical profiles included psychotic symptoms was the patients’ clinical deterioration over the course of their illness. Hence, Pick and Kraepelin applied the term dementia praecox because of the progressive impairment in cognitive function in young patients in contrast to senile dementia. In addition to establishing diagnosis for a disorder, their conceptualization of the illness hinted at its pathophysiology and defined a potential target for therapeutic intervention.

TABLE 1. Timeline of progress in preventive intervention research for schizophrenia

Enlarge table

Soon after that, however, Bleuler shifted the focus to the symptoms of the illness within a given episode and renamed the illness schizophrenia, referring to the schism between thought and affect in patients (18). As a result of the emphasis on cross-sectional symptomatology, the goal of future treatments would be to control symptoms rather than altering the course of the illness.

Efforts to Understand the Etiology and Pathophysiology of Schizophrenia

The serendipitous discovery of antipsychotics gave rise to the first scientifically credible pathophysiological theory of schizophrenia, the dopamine hypothesis (19). Previous theories (humoral, psychoanalytic, social learning, existential, constitutional, developmental, family system, infectious, immune), with the exception of the genetic theory, which was supported by epidemiologic genetic data, lacked substantive evidentiary bases (20–23). Since its inception five decades ago, the dopamine hypothesis has undergone multiple iterations (24–30). Despite these, while durable and heuristic, the dopamine hypothesis has been limited in its ability to fully explain the clinical pathology and course of schizophrenia and lead to innovative and better treatments.

A decade later, two competing pathophysiological theories emerged that subsequently framed the field’s thinking and research (31–34). The neurodevelopmental hypothesis of schizophrenia postulates that etiologic and pathogenic factors (such as genes and environmental insults), antedating the onset of the illness, disrupt the course of normal brain development, resulting in subtle alterations of specific cells, circuits, and their connectivity (31–33). This developmental disruption confers vulnerability to malfunction and the consequent manifestation of symptoms diagnostic of the illness. However, in contrast to other genetic neurodevelopmental disorders, such as autism, fragile X syndrome, or Down’s syndrome, the phenotype of schizophrenia is expressed after a latency period extending into the second and third decades of life. After its onset and over its course, the illness persists as a static encephalopathy, and the brain abnormalities only progress in the context of the aging process (35).

Although heuristic, the neurodevelopmental hypothesis of schizophrenia did not explain variation in the course of the illness after its onset or in response to treatment, and specifically its progressive nature. In addition, it fostered a therapeutic pessimism in which people with schizophrenia were “doomed from the womb” and had bleak prognoses regardless of treatment.

Because of these limitations and in an effort to accommodate the heterogeneity observed in the clinical presentations and research findings of schizophrenia, Crow proposed a “two-syndrome hypothesis” of schizophrenia (34) (Figure 1). Type I was characterized by acute episodes with mostly positive symptoms, minimal negative and cognitive symptoms, good antipsychotic treatment response, and indices of excessive dopamine activity. Type II was characterized by negative and cognitive symptoms (in addition to positive symptoms), poor treatment response, and evidence of brain structural pathology in vivo and postmortem. A novel feature of this hypothesis was the element of unidirectional progression of the illness from the type I to type II syndrome over time.

Shortly after publication of Crow’s two-syndrome hypothesis, McGlashan published a comprehensive review of the natural history of schizophrenia (8) that highlighted the clinical deterioration associated with the illness and specified that this occurred predominantly in the first 5 to 10 years of the illness. Subsequently, Wyatt (9) published an influential review that found that delays in treatment were associated with poorer outcomes. In addition, prospective studies of first-episode schizophrenia patients mapped the progressive nature of the illness and the therapeutic effects of treatment, beginning with the classic treatment study by May et al. (36). Concurrently, longitudinal MRI assessments of first-episode patients found progressive volumetric reduction of gray matter in specific brain regions and enlargement of the lateral ventricles and subarachnoid space (14, 37), in some cases reflecting illness course (38–41) and mitigated by treatment (39–43).

Studies of Natural History and Early Intervention

The consistently replicated correlation between longer duration of untreated psychosis and poorer outcome, along with the increasing reports of morphological changes demonstrated by longitudinal brain imaging studies, resonated with the historical descriptions of clinical deterioration by Kraepelin and subsequent long-term follow-up studies of (Manfred) Bleuler and Ciompi (8). These results prompted researchers to describe the natural history of schizophrenia as progressing through four stages of illness—premorbid, prodromal, onset/progressive, and chronic residual (44, 45). They also prompted researchers to redouble their efforts to develop a strategy to diagnose and treat patients as early in the course of their illness as possible.

The early identification and intervention strategy for schizophrenia offered hope to patients and clinicians alike that treatment could possibly limit the chronic morbidity and disability of schizophrenia (46, 47) (Figure 2). However, two critical challenges had to be addressed to achieve this goal: 1) reducing the time between the patient’s onset of symptoms and their diagnosis and treatment, and 2) engaging patients in treatment to foster recovery and prevent relapses.

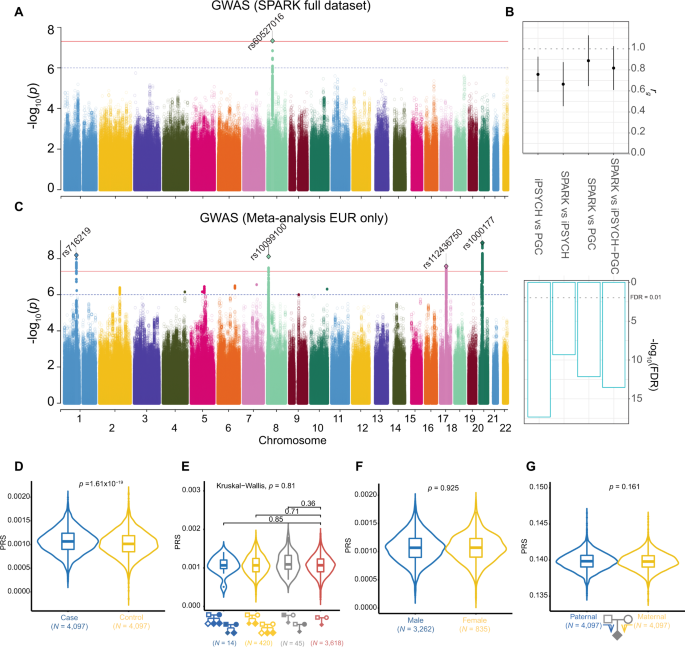

Educational attainment (EA) is moderately heritable1 and an important correlate of many social, economic, and health outcomes2,3. Because of its relationship with many health outcomes, measures of EA are available in most medical data sets. Partly for this reason, EA was the focus of the first large-scale genome-wide association study (GWAS) of a social-science phenotype4 and has continued to serve as a “model phenotype” for behavioral traits (analogous to height for medical traits). Genetic associations with EA identified via GWAS have been used in follow-up work examining biologizcal5 and behavioral mechanisms6,7 and genetic overlap with health outcomes8,9.

The largest (N = 293,723) GWAS of EA to date identified 74 approximately independent SNPs at genome-wide significance (hereafter, lead SNPs) and reported that a 10-million-SNP linear predictor (hereafter, polygenic score) had an out-of-sample predictive power of 3.2%10. Here, we expand the sample size to over a million individuals (N = 1,131,881). We identify 1,271 lead SNPs. In a subsample (N = 694,894), we also conduct genome-wide association analyses of variants on the X chromosome, identifying ten lead SNPs.

The dramatic increase in our GWAS sample size enables us to conduct a number of informative additional analyses. For example, we show that the lead SNPs have heterogeneous effects, and we perform within-family association analyses that probe the robustness of our results. Our biological annotation analyses, which focus on the results from the autosomal GWAS, reinforce the main findings from earlier GWAS in smaller samples, such as the role of many of the prioritized genes in brain development. However, the newly identified SNPs also lead to several new findings. For example, they strongly implicate genes involved in almost all aspects of neuron-to-neuron communication.

We found that a polygenic score derived from our results explains around 11% of EA variance. We also report additional GWAS of three phenotypes that are highly genetically correlated with EA: cognitive (test) performance (N = 257,841), self-reported math ability (N = 564,698), and hardest math class completed (N = 430,445). We identify 225, 618, and 365 lead SNPs, respectively. When we jointly analyze all four phenotypes using a recently developed method11, we found that the explanatory power of polygenic scores based on the resulting summary statistics increases, to 12% for EA and 7–10% for cognitive performance.

EA is an important dimension of socioeconomic status that features prominently in research by social scientists, epidemiologists and other medical researchers. EA is strongly related to a range of health behaviors and outcomes, including mortality1. For this reason, and because EA can be measured accurately at low cost, cohort studies used in genetic epidemiology and medical research routinely measure participants’ EA.

The most recent GWAS meta-analysis of EA had a combined sample size of ~1.1 million individuals2. Here we report and analyze results from an updated meta-analysis of EA in a combined sample nearly three times larger (N = 3,037,499). The increase comes from expanding the sample for the association analyses from 23andMe from ~365,000 to ~2.3 million genotyped research participants. As before, our core analysis is a GWAS of autosomal SNPs. Our updated meta-analysis identifies 3,952 approximately uncorrelated SNPs at genome-wide significance compared to 1,271 in the previous study. The larger sample size yields more accurate effect-size estimates that allow us to construct a genome-wide PGI (also called a polygenic score) that has greater prediction accuracy, increasing the percentage of variance in EA explained from 11–13% to 12–16%, depending on the validation sample, an increase of approximately 20%. In meta-analyses of the expanded 23andMe sample and the UK Biobank (UKB)3, we also conduct an updated GWAS of the X chromosome (N = 2,713,033) and the first large-scale ‘dominance GWAS’ (i.e., a SNP-level GWAS of dominance deviations) of EA on the autosomes (N = 2,574,253). In our updated X-chromosome GWAS, we increase the number of approximately uncorrelated genome-wide-significant SNPs from 10 to 57. Our dominance GWAS identifies no genome-wide-significant SNPs. Moreover, with high confidence, we can rule out the existence of any common SNPs whose dominance effects explain more than a negligible fraction of the variance in EA. Table 1 summarizes the GWASs conducted in this paper and compares them to previous large-scale GWASs of educational attainment.

A Common Genetic Variant in the Neurexin Superfamily

Member CNTNAP2 Increases Familial Risk of Autism

Dan E. Arking,1 David J. Cutler, 1 Camille W. Brune, 2 Tanya M. Teslovich,1 Kristen West, 1 Morna Ikeda,1

Alexis Rea,1 Moltu Guy,1 Shin Lin, 1 Edwin H. Cook Jr., 2 and Aravinda Chakravarti 1,*

Autism is a childhood neuropsychiatric disorder that, despite exhibiting high heritability, has largely eluded efforts to identify specific

genetic variants underlying its etiology. We performed a two-stage genetic study in which genome-wide linkage and family-based asso-

ciation mapping was followed up by association and replication studies in an independent sample. We identified a common polymor-

phism in contactin-associated protein-like 2 (CNTNAP2), a member of the neurexin superfamily, that is significantly associated with au-

tism susceptibility. Importantly, the genetic variant displays a parent-of-origin and gender effect recapitulating the inheritance of autism.

Autistic disorder (MIM 290850), first described by Kanner

in 1943, 1 is a pervasive developmental disorder character-

ized by a triad of marked features: impaired social interac-

tion, impaired language development, and restricted and

repetitive behavior and interests. A diagnosis of autism

can typically be made by 4 years of age. The prevalence is

approximately 20 per 10,000 for autistic disorder and 60

per 10,000 individuals for all autism spectrum disorders,

with males being 4 times as likely, as compared to females,

to be affected. 2 There is no doubt that autism presents a

significant disease burden.

Compelling evidence for a genetic basis for autism has

been provided by twin studies, demonstrating a signifi-

cantly higher concordance rate for monozygous versus di-

zygous twins, with an overall heritability of 80%–90%. 3

Consequently, it is expected that appropriate genomic

screens can identify susceptibility genes given the major

genetic component to familiality. With the availability of

new genotyping technologies that can survey the genome

at far higher resolution than before and large family collec-

tions with sufficient samples for both discovery and valida-

tion, we initiated a two-stage genome-wide study of autism

that is not limited by our current understanding of autism

pathophysiology.

For stage I, we selected 72 multiplex families (68 with 2

affected children and 4 with 3 affected children) compris-

ing 148 affected offspring and 292 individuals. We attemp-

ted to reduce phenotypic heterogeneity and increase the

genetic contribution by requiring all affected individuals

to be positive for autism on both ADI-R and ADOS instru-

ments4 and to have onset <36 months. This sampling was

in contrast to accepting only an ADI-R classification of au-

tism or accepting the broader ADOS classification of au-

tism spectrum disorder. No previously reported genetic

study of autism has had similarly strict phenotypic inclu-

sion criteria and equivalent sample size. All samples were

obtained from the National Institute of Mental Health

(NIMH) Autism Genetics Initiative.

We genotyped all samples by using Affymetrix 500K ar-

rays with genotypes inferred via the Affymetrix BRLMM

genotyping algorithm at the default settings. We used rel-

atively stringent quality control cut-offs for including

SNPs in our analyses, because even moderate missing

data or error rates increase false-positive linkage and fam-

ily-based association tests such as the transmission disequi-

librium test (TDT). 5 Specifically, SNPs with >10% missing

data, >1% Mendelian error, and lack of fit to Hardy-Wein-

berg proportions (p < 0.001) were excluded from analysis,

leaving 72% (336,121 of 468,411) of the data on autosomal

SNPs for further analysis. One family was excluded because

of Mendelian errors arising from maternal incompatibility,

and one child was excluded because he was incompatible

with both parents, resulting in 78 sib-pairs and 145 par-

ent/child trios that we included in the analyses.

Genome-wide association analysis with the TDT was per-

formed for both single-SNP and haplotypes with EATDT, 6

and no genome-wide significant SNPs or haplotypes were

identified. However, under a scenario in which multiple

unlinked variants within a locus contribute to autism

susceptibility, as opposed to a single variant of large effect,

the incorporation of traditional linkage data can be of

great benefit. Indeed, genome-wide linkage analysis by

MERLIN 7 revealed two loci with LOD scores above 2: one

at chromosome 7q35 (maximum LOD score 3.4 at 151.4–

154.4 cM; Figure 1A) and the second at chromosome

10p13–14 (maximum LOD score 2.9 at 26.6–34.5 cM).

The peak at 7q35 is genome-wide significant and is a novel

finding for strictly defined autism, though it is in the same

region that has been previously identified as a possible lan-

guage quantitative trait locus (QTL) in autism families. 8

TDT in the 1-LOD genetic interval under the chromosome

7q35 linkage peak revealed a single SNP, rs7794745, with

significant association with autism (p < 2.14 3 105 )

(Figure 1B), even after correcting for the number of SNPs

tested under the linkage peak by permutation (p <

0.006). rs7794745 had data completeness of 99.7%, no

Cognitive deficits are now considered a central feature of schizophrenia. Impairments in some domains are present before the emergence of the hallmark positive symptoms of the illness (CitationDavidson et al 1999; CitationCornblatt et al 1999) and moderate to severe impairments across most cognitive domains are detectable at the time of the first episode (CitationBilder et al 2000; CitationSaykin et al 1994) and appear stable from emergence of the first episode until middle age (CitationRund 1998).

Schizophrenia is associated with impairments across a number of cognitive domains. The breadth of this impairment has led some to conclude that it is a disease with a global profile of neuropsychological impairment (CitationBlanchard and Neale 1994; CitationDickinson et al 2004). Some evidence, however, suggests that there are discrete domains of cognitive impairment. For example, CitationBilder and colleagues (2002) found mild to moderate deficits in attention, verbal fluency, working memory, and processing speed, with superimposed severe deficits in declarative verbal memory and executive functioning. Other work suggests that discrete cognitive domains have differential correlates with symptom and functional domains. The argument over generalized or specific impairments is clouded by the fact that there is not a clear neuropsychological signature of schizophrenia. That is, most schizophrenia patients demonstrate at least some cognitive impairment, but, like other aspects of the illness, the severity and breadth of these impairments vary across patients. A rather unique feature of cognitive deficits, as compared to other characteristics of schizophrenia, is that they remain relatively stable within the same patient over time; they are generally consistent in severity and topography across changes in a patient’s clinical status (CitationHarvey et al 1990). Below, the types of impairments are described in detail.

General intelligence

Patients with schizophrenia have, as a group, lower Intelligence Quotient (IQ) scores than the general population. This difference is evident prior to the first episode of psychosis, with patients on the schizophrenia spectrum showing poorer performance on general IQ and non-verbal reasoning in particular (Reichenberg et al 2006). As young as age 8, poor performance on the Coding subtest of the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children, which is a measure of processing speed, distinguishes individuals who later develop schizophrenia spectrum disorders from those who do not (Sorensen et al 2006). Further evidence suggests that patients not only have lower IQ prior to and at first episode, but declines in IQ occur after the diagnosis (Seidman et al 2006). Even in schizophrenia patients who have seemingly normal cognitive skills, based on the rank of their scores in the population distribution, might still be impaired when considering their performance relative to their expected performance from expected IQ (Reichenberg et al 2005). Further, when matched to healthy control subjects on full scale IQ score, patients with schizophrenia still evidence impairment in specific neuropsychological domains not traditionally assessed with standardized IQ batteries (Wilk et al 2005).

Mutations of the transcription factor 4 (TCF4) gene cause mental retardation with or without associated facial dysmorphisms and intermittent hyperventilation. Subsequently, a polymorphism of TCF4 was shown in a genome-wide association study to slightly increase the risk of schizophrenia. We have further analysed the impact of this TCF4 variant rs9960767 on early information processing and cognitive functions in schizophrenia patients. We have shown in a sample of 401 schizophrenia patients that TCF4 influences verbal memory in the Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test. Contrary to expectations, carriers of the schizophrenia-associated allele showed better recognition, thus indicating that while TCF4 influences verbal memory, the TCF4-mediated schizophrenia risk is not determined by the influence of TCF4 on verbal memory. TCF4 does not impact on various other cognitive functions belonging to the domains of attention and executive functions. Moreover, in a pharmacogenetic approach, TCF4 does not modulate the improvement of positive or negative schizophrenia symptoms during treatment with antipsychotics. Finally, we have assessed a key electrophysiological endophenotype of schizophrenia, sensorimotor gating. As measured by prepulse inhibition, the schizophrenia risk allele C of TCF4 rs9960767 reduces sensorimotor gating. This indicates that TCF4 influences key mechanisms of information processing, which may contribute to the pathogenesis of schizophrenia.

Background

The combined analysis of several large genome-wide association studies identified the basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) transcription factor TCF4 as one of the most significant schizophrenia susceptibility genes. Its function in the adult brain, however, is not known. TCF4 belongs to the E-protein subfamily known to be involved in neurodevelopment. The messenger RNA expression of Tcf4 is sustained in the adult mouse brain, suggesting a function in the adult nervous system. Tcf4 null mutant mice die perinatally, and haploinsufficiency of TCF4 in humans causes severe mental retardation.

Methods

To investigate the possible function of TCF4 in the adult central nervous system, we generated transgenic mice that moderately overexpress TCF4 postnatally in the brain to reduce the risk of developmental effects possibly interfering with adult brain functions. Tcf4 transgenic mice were characterized with molecular, histological, and behavioral methods.

Results

Tcf4 transgenic mice display profound deficits in contextual and cued fear conditioning and sensorimotor gating. Furthermore, we show that TCF4 interacts with the neurogenic bHLH factors NEUROD and NDRF in vivo. Molecular analyses revealed the dynamic circadian deregulation of neuronal bHLH factors in the adult hippocampus.

Conclusions

We conclude that TCF4 likely acts in concert with other neuronal bHLH transcription factors contributing to higher-order cognitive processing. Moderate transcriptional deregulation of Tcf4 in the brain interferes with cognitive functions and might alter circadian processes in mice. These observations provide insight for the first time into the physiological function of TCF4 in the adult brain and its possible contributions to neuropsychiatric disease conditions.

Background: Schizophrenia patients are typically found to have low IQ both pre- and post-onset, in comparison to the general population. However, a subgroup of patients displays above average IQ pre-onset. The nature of these patients' illness and its relationship to typical schizophrenia is not well understood. The current study sought to investigate the symptom profile of high-IQ schizophrenia patients.

Methods: We identified 29 schizophrenia patients of exceptionally high pre-morbid intelligence (mean estimated pre-morbid intelligence quotient (IQ) of 120), of whom around half also showed minimal decline (less than 10 IQ points) from their estimated pre-morbid IQ. We compared their symptom scores (SAPS, SANS, OPCRIT, MADRS, GAF, SAI-E) with a comparison group of schizophrenia patients of typical IQ using multinomial logistic regression.

Results: The patients with very high pre-morbid IQ had significantly lower scores on negative and disorganised symptoms than typical patients (RRR=0.019; 95% CI=0.001, 0.675, P=0.030), and showed better global functioning and insight (RRR=1.082; 95% CI=1.020, 1.148; P=0.009). Those with a minimal post-onset IQ decline also showed higher levels of manic symptoms (RRR=8.213; 95% CI=1.042, 64.750, P=0.046).

Conclusions: These findings provide evidence for the existence of a high-IQ variant of schizophrenia that is associated with markedly fewer negative symptoms than typical schizophrenia, and lends support to the idea of a psychosis spectrum or continuum over boundaried diagnostic categories.

Background

Social cognitive impairment is common in schizophrenia, but it is unclear if it is present in individuals with high IQ. This study compared theory of mind (ToM) in schizophrenia participants with low or high IQ to healthy controls.

Methods

One hundred and nineteen participants (71 healthy controls, 17 high IQ (IQ ≥115), and 31 low IQ (IQ ≤95) schizophrenia participants) were assessed with the Movie for the Assessment of Social Cognition, providing scores for total, cognitive, and affective ToM, along with overmentalizing, undermentalizing, and no-mentalizing errors. IQ was measured with Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence; clinical symptoms with the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale.

Results

Healthy controls performed better than the low IQ schizophrenia group for all ToM scores, and better than the high IQ schizophrenia group for the total score and under- and no-mentalizing errors. The high IQ group made fewer overmentalizing errors and had better total and cognitive ToM than the low IQ group. Their number of overmentalizing errors was indistinguishable from healthy controls.

Conclusion

Global ToM impairment was present in the low IQ schizophrenia group. Overmentalizing was not present in the high IQ group and appears related to lower IQ. Intact higher-level reasoning may prevent the high IQ group from making overmentalizing errors, through self-monitoring or inhibition. We propose that high IQ patients are chiefly impaired in lower-level ToM, whereas low IQ patients also have impaired higher-level ToM. Conceivably, this specific impairment could help explain the lower functioning reported in persons with intact IQ.

Keywords:

Previous article View issue table of contents Next article

1. Introduction

Cognitive impairments are considered core features of schizophrenia [Citation1–4], and both social and nonsocial cognition show inter-individual heterogeneity [Citation4–6]. The two types of cognitive impairments are related [Citation5], exemplified by social cognition serving as a mediator of the association between nonsocial cognition and functional outcome [Citation7]. Furthermore, whereas social cognitive impairments can be seen in patients with normal-range nonsocial cognition, normal-range social cognition and impaired nonsocial cognition are rarely seen together [Citation8]. This ‘single dissociation’ could suggest that normal-range nonsocial cognition is necessary, but not sufficient, for intact social cognition.

Among the social cognitive domains, theory of mind (ToM) has the greatest impact on functional outcomes [Citation9]. ToM is the ability to infer the mental states of others, considered to be a complex, higher-level cognitive process which is dependent on lower-level processes, such as emotion perception [Citation10,Citation11] and basic nonsocial cognition [Citation11,Citation12]. It can be divided into two components: cognitive ToM, attributing thoughts, knowledge and plans, and affective ToM, attributing emotional states [Citation13,Citation14]. In clinical populations, researchers often distinguish between three error-types that people can make when solving ToM tasks. These are overmentalizing, i.e. a propensity to excessively attribute mental states and intentions, undermentalizing, i.e. reduced ability to understand and attribute mental states, and lack of mentalizing (or ‘no-mentalizing’), i.e. entirely failing to attribute mental states [Citation15,Citation16].

A recent meta-analysis concluded that there are moderate associations between various domains of nonsocial cognition and ToM in schizophrenia without significant differences between domains [Citation17]. Vaskinn et al. [Citation11] found associations between ToM and a nonsocial composite score, accounting for between 8 and 18% of the variance in different ToM subscores. In a follow-up study of the specific neuropsychological tests included in that composite score, Sjølie et al. [Citation12] reported that no single neuropsychological test, including a measure of IQ, uniquely contributed to ToM.

To better account for the cognitive heterogeneity observed in schizophrenia, there have been attempts at subgrouping based on nonsocial cognitive test scores. Studies indicate that cognitive heterogeneity in schizophrenia can be described by three distinct and reliably identified nonsocial cognitive subgroups [Citation18]: a relatively intact group, with good cognitive performance, an intermediate group, with moderate levels of overall impairment, and a globally impaired group, with severe cognitive deficits. These subgroups have been identified both empirically and clinically from intelligence trajectories [Citation19–21]. Whereas some authors [Citation22,Citation23] have found that the subgroups differ only in their level of overall impairment, others [Citation20,Citation21] have concluded that they also exhibit different cognitive profiles. They find that the relatively intact group has a profile more similar to healthy controls (HC) than to other schizophrenia subgroups. In this view, it is characterized by more isolated deficits than the other groups, for instance in executive functioning and attention [Citation20], however, see also, [Citation21].

Similarly, there are also reports of social cognitive heterogeneity in schizophrenia. Studies using cluster analysis have identified three subgroups, with relatively intact, impaired or very impaired social cognition [Citation24–26]. The relatively intact groups appear to have only subtle social cognitive deficits when compared to HCs [Citation25–27], and have better results than the low-performing groups on several measures of nonsocial cognition [Citation24,Citation25].

In conclusion, subgrouping based on IQ differences has been shown to be a useful tool in examining cognitive heterogeneity [Citation18,Citation28]. However, it is not known whether such subgroups have distinct social cognitive profiles. Developing a better understanding of social cognitive heterogeneity in schizophrenia is important. This could enable us to better tailor treatments to different groups of patients. ToM is a particularly interesting target in this respect due to its strong associations with functional outcomes.

The aim of the current study is to investigate subgroup differences in ToM, including ToM components and error-types, by comparing low and high IQ schizophrenia groups with a HC group. We hypothesize group differences for all ToM variables, with HC outperforming the high IQ schizophrenia group, which in turn will perform better than the low IQ schizophrenia group. We make no predictions for group differences in specific patterns of ToM performance, due to the mixed results described in the social cognition literature above.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Participants

Forty-eight participants (31 male, 17 female) with a DSM-IV diagnosis of schizophrenia (n = 34) or schizoaffective disorder (n = 14), selected from a larger sample [Citation11], were included, together with 71 HC (42 male, 29 female). We chose to include patients with schizoaffective disorder as their cognitive impairments are largely similar to those seen in schizophrenia [Citation29]. All were participants in the Thematically Organized Psychosis (TOP) study at the Norwegian Centre for Mental Disorders Research (NORMENT). Schizophrenia participants were recruited from in- and outpatient units at Oslo and Akershus University Hospitals.

Inclusion criteria were Norwegian as first language or all compulsory schooling in Norway and age 18–55 years. Exclusion criteria were neurological disease or having been hospitalized following a head trauma. For the current study, schizophrenia participants with an IQ of 115 or higher, as assessed with the subtests Similarities and Matrix Reasoning from Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence (WASI) [Citation30], were selected for the high IQ schizophrenia group, whereas participants with an IQ between 71 and 95 were selected for the low IQ schizophrenia group. The upper cutoff of 95 was chosen to achieve statistical power and to adhere to our previous studies [Citation23]. HCs from the same geographical area were randomly selected from national statistical records and invited by letter. They were screened with the Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders (PRIME-MD) [Citation31] interview and excluded if mental, neurological, or somatic disorder was present. Participants gave informed consent to participate in the study, which was approved by the Regional Ethical Committee. Clinical assessments were based on semi-structured interviews and chart reviews. Diagnostic assessments were conducted with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID-I) [Citation32] by medical doctors and psychologists who had completed a clinical training program from University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) [Citation33]. Cognitive assessments were conducted by psychologists or master level psychology students, trained by an experienced clinical psychologist (AV).

2.2. ToM measure

ToM was measured with the Norwegian version of the MASC test [Citation34]. It consists of a 15-minute video of two men and two women at a dinner party. Participants are asked to answer 45 multiple choice questions about the characters’ thoughts, feelings, and intentions. The test yields six scores, including a total score, MASCtot (range 0–45). The individual items were further divided into two ToM component categories, cognitive ToM (MASCcog, 0–26) and affective ToM (MASCaff, 0–18), as described in [Citation11]. In addition, the MASC test distinguishes between three different error types (range 0–45 for each score): overmentalizing (MASCexc), undermentalizing (MASCless), and no-mentalizing (MASCno).

2.3. Symptom measure

Symptoms were measured using the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) [Citation35]. The Wallwork/Fortgang five-factor model [Citation36] was chosen, as it has been shown to provide the best fit in several studies [Citation37–39]. It includes the factors positive (PANSSpos), negative (PANSSneg), disorganized (PANSSdis), excited (PANSSexc) and depressed (PANSSdep). Ranges are listed in

.

Table 1. Demographics and clinical features.

Download CSVDisplay Table

2.4. Statistical analyses

Analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 27th version (2020). The Kolmogorov–Smirnov–Lilliefors significance correction revealed non-normal scores in several cells. We therefore chose nonparametric statistics in all analyses. We applied six Kruskal Wallis H-tests to determine whether the low IQ schizophrenia, high IQ schizophrenia, and HC groups differed for any of the MASC scores, followed by a post hoc Dunn-Bonferroni comparison to identify differences between each pairing of the three groups. Effect sizes were calculated as eta squared (η2) for the Kruskal Wallis H-tests and as Hedge’s g for the post hoc tests. We adjusted the p-values for the two ToM components (p = 0.05/2 = 0.025) and the three error types (p = 0.05/3 = 0.017). The Hettmansperger and McKean method [Citation40] – a nonparametric alternative to the ANCOVA – was used to investigate whether any significant group difference in ToM between the two schizophrenia groups remained after controlling for differences in symptom load. Due to its high rate of type II errors, nonsignificant results should be interpreted with some caution.

Converging evidence for a pseudoautosomal cytokine receptor gene locus in schizophrenia

Schizophrenia is a strongly heritable disorder, and identification of potential candidate genes has accelerated in recent years. Genomewide scans have identified multiple large linkage regions across the genome, with fine-mapping studies and other investigations of biologically plausible targets demonstrating several promising candidate genes of modest effect. The recent introduction of technological platforms for whole-genome association (WGA) studies can provide an opportunity to rapidly identify novel targets, although no WGA studies have been reported in the psychiatric literature to date. We report results of a case-control WGA study in schizophrenia, examining approximately 500 000 markers, which revealed a strong effect (P=3.7 x 10(-7)) of a novel locus (rs4129148) near the CSF2RA (colony stimulating factor, receptor 2 alpha) gene in the pseudoautosomal region. Sequencing of CSF2RA and its neighbor, IL3RA (interleukin 3 receptor alpha) in an independent case-control cohort revealed both common intronic haplotypes and several novel, rare missense variants associated with schizophrenia. The presence of cytokine receptor abnormalities in schizophrenia may help explain prior epidemiologic data relating the risk for this illness to altered rates of autoimmune disorders, prenatal infection and familial leukemia.

The dystrobrevin-binding protein 1 gene (DTNBP1) has been regarded as a susceptibility gene for schizophrenia. Recent studies have investigated its role on cognitive function that is frequently impaired in schizophrenia patients, and generated inconsistent results. The present study was performed to elucidate effects of genetic variations in DTNBP1 on various cognitive domains in both schizophrenia patients and healthy subjects. Comprehensive neuropsychological tests were administered to 122 clinically stable schizophrenia patients and 119 healthy subjects. Based on positive findings reported in previous association studies, six SNPs were selected and genotyped. Compared to healthy subjects, schizophrenia patients showed expected lower performance for all of the cognitive domains. After adjusting for age, gender, and educational level, four SNPs showed a nominally significant association with cognitive domains. The association of rs760761 and rs1018381 with the attention and vigilance domain remained significant after applying the correction for multiple testing (P < 0.001). Similar association patterns were observed both, in patients and healthy subjects. The observed results suggest the involvement of DTNBP1 not only in the development of attention deficit of schizophrenia, but also in the inter-individual variability of this cognitive domain within the normal functional range. © 2012 Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

Abstract

Autistic traits are highly heritable and characterized by social deficits. Common genetic variants of the autism-related CNTNAP2 gene have been linked with social impairments, but the neural substrates are poorly understood. In the present study, we investigated the genetic effect of common variants of CNTNAP2 (rs2710102 and rs7794745) on gray matter volume and its association with social performance among 442 healthy participants. Our results showed that individuals with rs2710102 GG homozygotes had smaller left superior temporal gyrus (STG)/insular volume than A-allele carriers (AA and AG), while individuals with rs7794745 TT and AT showed smaller right parahippocampal, right STG/insular, and left inferior parietal lobule (IPL) cortex volume than those with rs7794745 AA. Smaller volume of the STG/insular and parahippocampal cortex was associated with poorer social performance. An indirect effect of CNTNAP2 rs7794745 and rs2710102 genotype on the social performance was mediated by the STG/insular cortex and parahippocampal cortex volume. These findings provided insight into the genetic effect of CNTNAP2 variants on social behavior, which may be moderated by the temporal cortex.

Introduction

Autism spectrum disorders (ASD) are a group of heterogeneous neuro- developmental disorders, characterized by social deficits and repetitive behavior [1]. As disorders with highly heritability and heterogeneity [2], the ASD have been linked with multiple genes variants, either common variants or rare variants [[3], [4], [5]]. Of note, the contact in-associated protein-like 2 (CNTNAP2) was among the first genes associated with the increased risk of ASD for both rare and common variation.

CNTNAP2 is one of the largest protein coding genes in the human genome and encodes contactin-associated protein-like 2, a member of the neurexin super family of transmembrane proteins, which is crucial for brain development [[6], [7], [8]]. CNTNAP2 is expressed in frontal cortex and the anterior temporal cortex, important for social function and language, such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) [9], schizophrenia [10,11], and particularly with autism spectrum disorders (ASD) [[12], [13], [14]].

Solid evidence showing the relationship between ASD and CNTNAP2 is that CNTNAP2 knock-out mice present behavioral phenotypes reminiscent of ASD, including abnormal-social behavior and inflexible motor movements. In human, copy number variant (CNV) deletions of CNTNAP2 were also was associated with ASD [15]. Besides, common genetic variants were also linked with ASD. In particular, two single nucleotide polymorphism (SNPs) rs2710102 and rs7794745 were most frequently reported associations with the risk of ASD [12,13]. Specially, the rs7794745 T and rs2710102C increased ASD risk. In general population, the rs7794745 T and rs2710102C were reported effect on early language development [[16], [17], [18]], which are common features and related with poor social performance in ASD [18,19].

Indeed, healthy individuals homozygous for both risk alleles, both rs7794745 T and rs2710102C, exhibited decreased language lateralization during a langue task (an increased activation in the right inferior frontal gyrus) [20]. The decreased language lateralization has also been observed in ASD [21]. Furthermore, more genetic-imaging studies were conducted to explore genetic effect of CNTNAP2 on brain structure [[22], [23], [24]] that the presumed risk genotypes of ASD exhibited reduced grey matter volume in the superior occipital gyrus and frontal cortex.

However, genetic effects of CNTNAP2 on brain structure have not been examined among Chinese population. Besides, although interesting findings, there is little research to explore the relationship between cerebral structure effect of CNTNAP2 and autistic related behavior directly. Exploring this relationship may be helpful to elucidate the pathological mechanisms of the polymorphism. In the present study, we investigated the effect of two most important common variants of CNTNAP2, rs2710102 and rs7794745, on brain structure among Chinese general population and its relationship with social performance.

The mind-blindness theory of autism spectrum conditions has been successful in explaining the social and communication difficulties that characterize these conditions but cannot explain the nonsocial features (the narrow interests, need for sameness, and attention to detail). A new theory, the empathizing–systemizing (E-S) theory, is summarized, which argues two factors are needed to explain the social and nonsocial features of the condition. This is related to other cognitive theories such as the weak central coherence theory and the executive dysfunction theory. The E-S theory is also extended to the extreme male brain theory as a way of understanding the biased sex ratio in autism. Etiological predictions are discussed, as are the clinical applications arising from the E-S theory.

The hypersystemizing theory of autism suggests that autistic individuals, on average, have superior attention to detail, and a stronger drive to systemize. Systemizing involves identifying input-operation-output relationships in order to analyse and build systems and to understand the laws that govern specific systems1. Several lines of evidence suggest that autistic individuals have intact or superior systemizing. This idea was noted in the earliest reports describing autism. In his 1944 paper describing autism2, Hans Asperger noted a proclivity for patterns and order in autistic children. Of one child, he writes, “He orders his facts into a system and forms his own theories even if they are occasionally abstruse.” He observes that another child had “specialised technological interests and knew an incredible amount about complex machinery,” while a third child “was preoccupied by numbers.” In Leo Kanner’s 1943 paper, he writes that the children with autism have “precise recollection of complex patterns and sequences3.”

These initial clinical observations have been quantified using different measures. For example, on a self-report measure of systemizing (the Systemizing Quotient – Revised, or the SQ-R)4, autistic adults, on average, score significantly higher than non-autistic individuals4,5. The same pattern of results is seen in autistic children, using the parent-report version of the SQ6. Systemizing is also highly correlated with aptitude in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM)7. Fathers and grandfathers of children with autism are significantly overrepresented in the field of engineering8. The same is true of mothers9. This is in line with higher rates of autism in geographical regions that have higher rates of people working in fields such as information technology, like Eindhoven in the Netherlands10. Further, autistic individuals are more likely to enrol in STEM majors (34.31%) compared to the general population (22.8%) and other learning disabilities (18.6%)11. STEM professionals also score significantly higher on measures of autistic traits (mean = 21.92, SD = 8.92) compared non-STEM professionals (mean = 18.92, SD = 8.48)12. Finally, unpublished work from Sweden suggests that high technical IQ in fathers increases risk for autism in children. A few studies have also investigated systemizing in other psychiatric traits and conditions, including schizotypy13 and anorexia nervosa14.

It is unclear if the link between autism and systemizing is due to underlying genetics or due to other non-biological factors (for example, people high in systemizing may be more aware of autism and hence more likely to seek a diagnosis). Here we directly test this using genome-wide association data from 51,564 research participants from 23andMe, Inc., a personal genetics company, and who completed the SQ-R. This study has the following aims: 1. To investigate the genetic architecture of systemizing, using the SQ-R; 2. To identify the genetic correlation between the SQ-R and psychiatric conditions (including autism) and psychological traits; 3. To identify enrichment in tissues, gene groups, and biological pathways.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6103885/In her 1936 report of paired-pulse blink inhibition in 13 Yale undergraduate men, Helen Peak described “quantitative variation in amount of inhibition of the second response incident to changes in intensity of the first stimulus which precedes by different intervals of time” (Peak, 1936). These observations appeared to lay dormant for much of the next 30 years, but there was a resurgence of interest in startle modulation in the 1960's, based primarily on findings from Howard Hoffman's group (e.g. Hoffman and Fleshler, 1963). Almost four decades after Peak's first report, and more than 100 years after prestimulus-induced reflex inhibition was first described by the Russian scientist, Sechenov, Frances Graham summarized the growing literature of weak prestimulation effects on startle magnitude and latency (e.g. Hoffman and Searle, 1968) in her 1974 Presidential Address to the Society for Psychophysiological Research (Graham, 1975; see Ison and Hoffman, (1983) for more historical background). This set the stage for David Braff's 1978 report of findings from Enoch Callaway's laboratory, extending Graham's parametric findings of startle inhibition, and demonstrating a relative loss of prestimulus effects on startle in 12 schizophrenia patients (Braff et al., 1978). Braff and colleagues interpreted this loss to be “consistent with a dysfunction in… early protective mechanisms which would correlate with information overload and subsequent cognitive disruption in schizophrenia.” They also noted that deficits observed in patients might reflect a range of issues not specific to schizophrenia, including “global psychopathology… stress of hospitalization… [and] antipsychotic medications.”

It has been shown repeatedly that PPI is significantly impaired in various psychiatric disorders that show similar or overlapping deficits in attention, such as schizophrenia (e.g. Braff et al., 1978; Aggernaes et al., 2010; During et al., 2014), mania with psychosis (Perry et al., 2001), autism spectrum disorders (ASD) (McAlonan et al., 2002; Perry et al., 2007) and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (Grillon et al., 1996, 1998).

Theoretically, deficient information processing and impaired perceptual capacity in ADHD patients result in sensory overload which in turn may underlie ADHD symptoms, e.g., the inability to regulate attention and inhibit distraction of attention by irrelevant stimuli (Olincy et al., 2000; Holstein et al., 2013).

We hypothesized that both gating measures would be deficient in the psychostimulant-naïve state of the ADHD patients due to decreased prefrontal dopaminergic activity, and that treatment with MPH would ameliorate these deficiencies due to the increase in dopaminergic activity caused by MPH.

The absence of PPI and P50 suppression deficits in our patients in the psychostimulant-naïve state indicates no gating deficits. In turn, this suggests that the difficulties to inhibit distraction of attention by irrelevant stimuli that many patients with (adult) ADHD report, have a different origin than the theoretical causes of sensory overload frequently reported in studies on patients with schizophrenia.

Consistent with increased neural maturity and partially remitted symptomatology, our results indicate intact sensorimotor gating for both tasks in adult ADHD with no comorbidity, independent of the subjects' gender and whether ADHD subjects were receiving ongoing stimulant treatment or not. Reduced PPI at 120-ms lead intervals, on the other hand, was recorded in a subset of 10 ADHD subjects who were taken off their prescribed regular stimulants for 24 h and tested in a randomized counterbalanced order for on vs. off medication. However, our data remained inconclusive as to whether this observation constitutes beneficial treatment or acute stimulant withdrawal effects on sensorimotor gating.

Sensorimotor gating is the process by which one filters out relevant from irrelevant information, a process that is deficient in multiple neuropsychiatric disorders including TS (Castellanos et al., 1996). Prepulse inhibition (PPI) is a measure of sensorimotor gating, in which response, or startle, to a stimulus (pulse) is diminished when the stimulus is preceded by a smaller stimulus (prepulse) (Swerdlow, 2013; Swerdlow and Sutherland, 2005). Disruption of this normal inhibition of startle is consistent with deficient sensorimotor gating. Structures relevant to PPI include the frontal dopaminergic pathways and striatum (Swerdlow et al., 2001). Pharmacological interventions that restore normal PPI typically have good predictive validity for efficacy in multiple neuropsychiatric disorders including TS. PPI has a relevant noradrenergic component as disruptions to PPI can be restored with clonidine, an alpha-2 agonist, and a separable dopaminergic component (Swerdlow et al., 2006). In addition to the predictive validity, it has been suggested that PPI models may also have possible face validity for TS, perhaps modeling the sensory component or premonitory urge present in TS that cannot be filtered or gated (Swerdlow and Sutherland, 2005).

Palinopsia (Greek: palin for "again" and opsia for "seeing") is the persistent recurrence of a visual image after the stimulus has been removed.[1] Palinopsia is not a diagnosis; it is a diverse group of pathological visual symptoms with a wide variety of causes. Visual perseveration is synonymous with palinopsia.[dubious – discuss]

In 2014, Gersztenkorn and Lee comprehensively reviewed all cases of palinopsia in the literature and subdivided it into two clinically relevant groups: illusory palinopsia and hallucinatory palinopsia.[2] Hallucinatory palinopsia, usually due to seizures or posterior cortical lesions, describes afterimages that are formed, long-lasting, and high resolution. Illusory palinopsia, usually due to migraines, head trauma, prescription drugs, visual snow or hallucinogen persisting perception disorder (HPPD), describes afterimages that are affected by ambient light and motion and are unformed, indistinct, or low resolution.

The results of the study reveal that there was significant improvement in some cognitive function. Cognitive functions are improved at first follow-up and they improved continuously up to last follow-up that is at one month. It is observed that there was improvement in the primary disease. So, final score of the cognitive parameters is because of the resultant activity of direct drug action and improvement in the underlying disease.

Keywords: Antidepressants, fluoxetine, PGI memory scale