InMemoriam

Celiacel

★★★★★

- Joined

- Feb 19, 2022

- Posts

- 8,732

Our concurrent inceldom predicament aided by the current shift of sexual selection dynamics and hypergamy paradigm will inevitably lead an evolutionary mass extinctions events whipping out the incel genome due to lack of reproduction alone.

Said events causes a hierarchical reform in the looks department (of men)

Which in turns would result in normies taking our spot as out rightful successors

@shii410 correctCope because the incel genome was always passed down through foids not ugly retards

This is the main argument put forward by reproductive reductionists and female supremacists, to support their gynocentric narrative known as the golden uterus; their misandristic views of men as subhumans on the basis that having a uterus makes an individual more biological valuable!

Deliberately negelcting innate male advantages, downplaying the value of roles outside of the female reproductive function when it comes to their contribution to evolutionary success.

Evolutionary success is far much complicated than just asserting that it all comes down to reproduction.

Reproduction dependent on multiple activities to establize it occurance; an organism must survive to mate and reproduce, as it cannot find a mate and then reproduce then it is dead. (reproduction does not happen without survival)

Yes reproduction is essential, but it is not the only essential activity required to propagate the genome.

An organism has to survive long enough to reproduce an optimal number of times and then raise the offspring to sexual maturity, whom also have to then survive, mate and then raise their offspring. If this does not occur to a sufficient degree, then any reproduction that does occur is insufficient to perpetuate the lineage and it dies out.

Men and women are merely two reproductive components in one reproductive system, that the genome fabricates to perpetuate itself.

Each sex is an interdependent component in a system that the genome encodes to perpetuate itself; It has nothing to do with superiority or supremacy and everything to do with a dynamic adaptive system optimising the propagation of the genome that encoded it over time and across environments, by developing complementary components with complementary strengths and roles, that functionally serve a purpose greater than either component on their own.

Further implications:

Disentangling Genetic and Environmental Factors

Normal Facial Surface Morphology

Standardized clinical facial charts/tables/measures are routinely used for newborns (e.g., head circumference, body length) and other specialties such as, ophthalmology and orthodontics. There are many published norms for different racial/population groups used to identify individuals who fall within the normal range and identify any facial dysmorphologies.

The soft tissue facial variation has been explored in a large Caucasian population of 15-year-old children (2514 females and 2233 males) recruited from the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC). Face height (28.8%), width of the eyes (10.4%) and prominence of the nose (6.7%) explained 46% of total facial variance (Toma et al., 2012). There were subtle differences between males and females in relation to the relative prominence of the lips, eyes, and nasal bridges including minor facial asymmetries (Toma et al., 2008, 2012; Wilson et al., 2013; Abbas et al., 2018). The dimorphic differences appear to follow similar patterns in different ethnic groups (Farnell et al., 2017).

Heritability

Facial morphology refers to a series of many different complex traits, each influenced by genetic and environmental factors. In particular, the strong effects that genetic variation can have on facial appearance are highlighted by historical portraits of the European royal family, the Habsburgs (1438–1740). Presumably because of frequent consanguineous marriages, later Habsburg rulers often had extreme facial phenotypes such as the characteristic “Habsburg” jaw (mandibular prognathism). Indeed, the last Habsburg King of Spain, Charles II, was reported to have had difficulties eating and speaking because of facial deformities. The influence of genetic variation is also evident in non-consanguineous families, where dental and facial characteristics are common among siblings and passed on from parents to their offspring (Hughes et al., 2014). Twin studies have historically been employed to explore the relative genetic and environment influence on facial shape exploiting the genetic differences between monozygotic and dizygotic twins (Visscher et al., 2008). Twin studies suggest that 72–81% of the variation of height in boys and 65–86% in girls is due to genetic differences with the environment explaining 5–23% of the variation (Jelenkovic et al., 2011). Similar levels of genetic-environmental contributions have been reported for some facial features. Predominantly genetic influences have been reported for anterior face height, relative prominence of the maxilla and mandible, width of the face/nose, nasal root shape, naso-labial angle, allometry and centroid size (Carels et al., 2001; Carson, 2006; Jelenkovic et al., 2010; Djordjevic et al., 2013a,b, 2016; Cole et al., 2017; Tsagkrasoulis et al., 2017). Substantial heritability estimates for facial attractiveness and sexual dimorphism (0.50–0.70 and 0.40–0.50), respectively (Mitchem et al., 2014), further demonstrate the strong genetic influences on facial phenotypes.

Contrastingly, previous estimates suggest that antero-posterior face height, mandibular body length, ramus height, upper vermillion height, nasal width and maxillary protrusion are more strongly influenced by environmental factors (Jelenkovic et al., 2010; Djordjevic et al., 2016; Sidlauskas et al., 2016; Cole et al., 2017; Tsagkrasoulis et al., 2017). However, it is important to note that heritability estimates for specific traits can be inconsistent for a number of reasons including heterogeneity across study populations, small sample sizes, research designs, acquisition methods and the differing types of analyses employed.

Environmental Influences

From the moment of conception, the parental environment can influence the development of the fetus. Facial development occurs very early at a time when the mother is not always aware that she is pregnant. The developing fetus may be subject to adverse environments at home, in the workplace or through lifestyle activities (smoking, alcohol and drug intake, allergens, paint, pest/weed control, heavy metals, cleaning, body products such as perfumes and creams). Many of these substances can cross the placenta (Naphthalene a volatile polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon related to solvent emissions is present in household products and pesticides – Mirghani et al., 2015; Nicotine – Wickström, 2007; Drugs and alcohol – Lange et al., 2014). There is evidence to suggest that the effects of some of these substances can also continue post-natally through breast milk fed to the new-born (heavy metals – Caserta et al., 2013; Dioxin – Rivezzi et al., 2013). Some of these early factors such as nictotine and alcohol may potentially influence on early neurological development (Wickström, 2007). Indeed, there is evidence to suggest that high levels of prenatal alcohol exposure can influence facial morphology; individuals with fetal alcohol syndrome disorders can present with facial abnormalities (Hoyme et al., 2016) as well as other developmental anomalies such as caudate nucleus asymmetry and reduced mass of the brain (Suttie et al., 2018). However, the effects of lower levels of prenatal alcohol exposure on facial morphology are less clear (Mamluk et al., 2017; Muggli et al., 2017; Howe et al., 2018c). Similarly, it has been hypothesized that maternal smoking may influence facial morphology and be a risk factor for cleft lip and palate (Xuan et al., 2016) with DNA methylation a possible mediator (Armstrong et al., 2016). However, to date one study has indicated that maternal smoking may interact with the GRID2 and ELAVL2 genes resulting in cleft lip and palate (Beaty et al., 2013). However, previous studies investigating gene-smoking interactions in the etiology of birth defects have produced mixed results (Shi et al., 2008). Another mechanism via which environmental influences can affect facial traits is natural selection, where certain facial traits may have beneficial effects on reproductive fitness. For example, there is evidence that nose shape has been under historical selection in certain climates (Weiner, 1954; Zaidi et al., 2017).

Generally, most modifiable environmental factors have only subtle effects on the face. However, it is important to note that stochastic chance events such as facial trauma, infections, burns, tumors, irradiation and surgical procedures can all have a significant impact on facial development and consequently facial morphology.

Craniofacial Shape Gene Discovery

The first wave of genetic studies of craniofacial Mendelian traits were based on linkage or candidate gene studies of genetic loci known to be involved in craniofacial development or genetic syndromes affecting the face. Down syndrome, cleft lip and/or palate, Prader-Willi syndrome, and Treacher Collins syndrome can all present with facial abnormalities and genetic loci associated with them have been studied in relation to normal facial development (Boehringer et al., 2011; Brinkley et al., 2016).

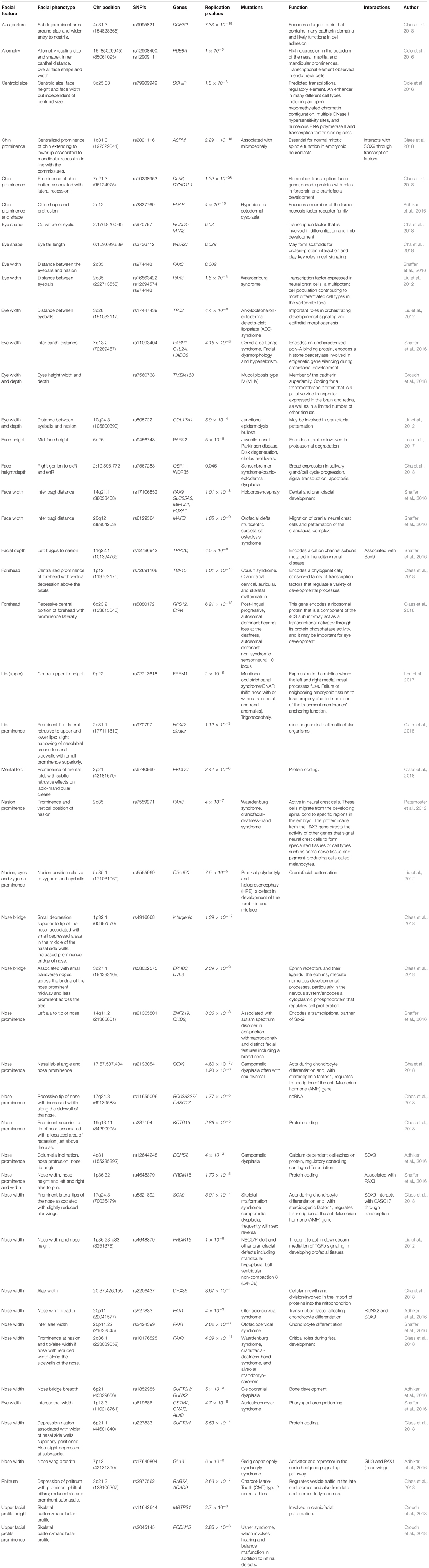

Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have investigated the association between normal facial variation and millions of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs). GWAS studies coupled with high-resolution three-dimensional imaging of the face have enabled the study of the spatial relationship of facial landmarks in great detail. Over the last 6 years there has been significant progress with 9 published GWAS which have identified over 50 loci associated with facial traits (Liu et al., 2012; Paternoster et al., 2012; Adhikari et al., 2016; Cole et al., 2016; Shaffer et al., 2016; Lee et al., 2017; Cha et al., 2018; Claes et al., 2018; Crouch et al., 2018). The genes and broad regional associations are shown in Table 2 (ordered by facial feature and chromosome) and Figure 1 (showing facial region). For detailed information on the biological basis of individual genes, the reader should refer to the original articles. Different facial measures have been applied to facial images obtained from a variety of acquisition systems (2D and 3D). Genes are likely to influence more than one facial trait. For instance, the PAX3 gene is associated with eye to nasion distance, prominence of the nasion and eye width, side walls of the nose, and prominence of nose tip. Similarly, the naso-labial angle will be associated with nose prominence and DCHS2 is linked to both traits.

Table 2

TABLE 2. List of genes and SNP’s associated with normal variation ranked by chromosome position (GWAS).

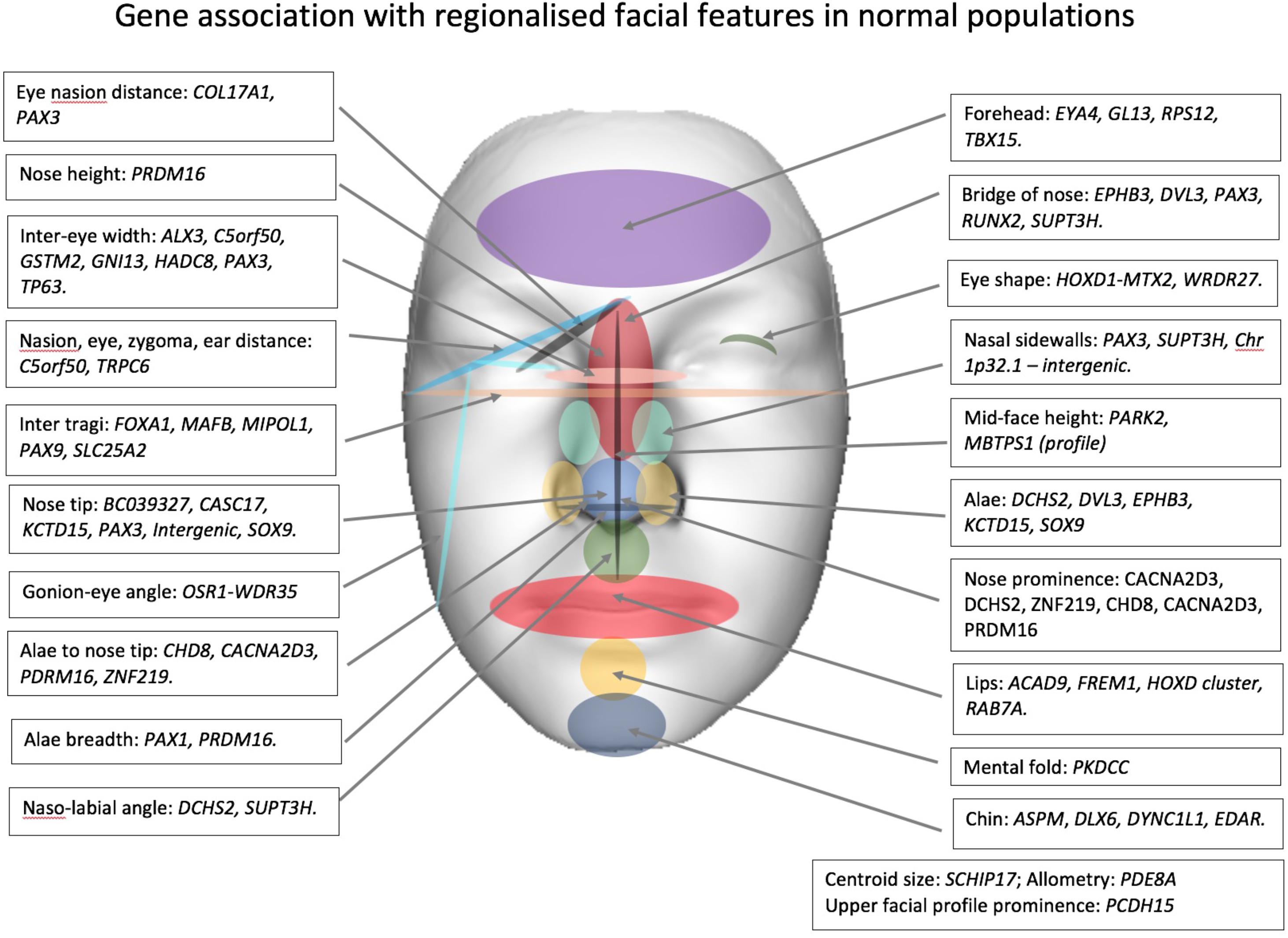

Figure 1

FIGURE 1. Gene association with regionalized facial features in normal populations.

Some reported genes appear to influence different parts of the face. PRDM16 is linked to the length and the prominence of the nose as well as the width of the alae, SOX9 is thought to be related to the shape of the ala and nose tip, variation in SUPT3H is thought to influence naso-labial angle and shape of the bridge of the nose, while centroid size (squared root of the squared distances of all landmarks of the face from the centroid) and allometry (relationship of size to shape) have been linked to PDE8A and SCHIP17 genes, respectively, (Cole et al., 2016). Eye width and ear – nasion distance and nasion -zygoma – eyes distances are linked to C5orf50. There is some evidence to suggest that there are additive genetic effects on nose shape involving SOX9, DCHS2, CASC17, PAX1, RUNX2, and GL13 and chin shape, SOX9 and ASPM. In addition, it is likely that one or more genes influence the whole shape of the face as well as more localized facial regions (Claes et al., 2018). A significant number of genes are integrally involved in cranial neural crest cells and patternation of the craniofacial complex (e.g., C5orf50, MAFB, and PAX3).

Understanding the Etiology of Craniofacial Anomalies

Identifying genetic variants influencing facial phenotypes can lead to improved etiological understanding of craniofacial anomalies, advances in forensic prediction using DNA and testing of evolutionary hypotheses.

Non-syndromic cleft lip/palate (nsCL/P) is a birth defect with a complex etiology, primarily affecting the upper lip and palate (Mossey et al., 2009; Dixon et al., 2011). Previous studies have identified genes associated with both nsCL/P and facial phenotypes; such as variation in MAFB which is associated with face width in normal variation (Beaty et al., 2010, 2013; Boehringer et al., 2011; Liu et al., 2012; Peng et al., 2013; Shaffer et al., 2016). Furthermore, craniofacial sub-phenotypes have been observed in nsCL/P cases and their unaffected family members such as orbicularis oris muscle defects and facial shape differences supporting the existence of nsCL/P related sub-phenotypes (Stanier and Moore, 2004; Marazita, 2007; Neiswanger et al., 2007; Menezes and Vieira, 2008; Weinberg et al., 2009; Aspinall et al., 2014).

The important link between facial variation and nsCL/P is highlighted by a study comparing facial morphologies (linked to genes) of children with nsCL/P and unaffected relatives. There was reduced facial convexity (SNAI1), obtuse nasolabial angles, more protrusive chins (SNAI1, IRF6, MSX1, MAFB), increased lower facial heights (SNAI1), thinner and more retrusive lips and more protrusive foreheads (ABCA4-ARHGAP29, MAFB) in the nsCL/P relatives compared to controls. There was also greater asymmetry in the nsCL/P group (LEFTY1, LEFTY2, and SNAI1) (Miller et al., 2014).

There is evidence that nsCL/P genetic risk variants have an additive effect on philtrum width across the general population. This association suggests that developmental processes relating to normal-variation in philtrum development are also etiologically relevant to nsCL/P, highlighting the shared genetic influences on normal-range facial variation and a cranio-facial anomaly (Howe et al., 2018a).

Similarly, genetic variations associated with normal-range facial differences have been linked to genes involved in Mendelian syndromes such as TBX15 (Cousin syndrome) (Shaffer et al., 2017; Claes et al., 2018), PAX1 (Otofaciocervical syndrome) (Shaffer et al., 2016) and PAX3 (Waardenburg syndrome) (Paternoster et al., 2012). It has been hypothesized that deleterious coding variants may directly cause congenital anomalies while non-coding variants in the same genes influence normal-range facial variation via gene expression pathways (Shaffer et al., 2017; Freund et al., 2018).

Shared genetic pathways may influence both normal-range variation in facial morphology and craniofacial anomalies. Disentangling these shared pathways can improve understanding of the biological processes that are important during embryonic development.

Estimating Identity

Anthropology and Human History

Over time, facial morphology across populations has been influenced by various factors, such as migration, mate-choice, survival and climate, which have contributed to variation in facial phenotypes. Genetic and facial phenotype data can be used to improve understanding of human history.

Ancestry and Genetic Admixture

Ancestry and physical appearance are highly related; it is often possible to infer an individual’s recent ancestry based on physically observable features such as facial structure and skin color. Indeed, previous studies have demonstrated that self-perceived and genetically inferred ancestry are associated with facial morphology, particularly with regards to the shape of the nose (Dawei et al., 1997; Le et al., 2002; Farkas et al., 2005; Claes et al., 2014). Facial morphological differences relating to ancestry are well-characterized when comparing individuals from distinct populations, but distinct differences remain even within more ancestrally homogeneous populations.

Historical migrations, such as the European colonization of Latin America, led to genetic admixture (breeding between individuals from previously isolated populations) (Hellenthal et al., 2014), which greatly influenced the facial morphology of the Latin American population. Indeed, modern day Latin Americans have mixed African, European and Native American ancestry, with genetic admixture highly predictive of physical appearance. For this reason, ancestral markers are often included in facial prediction models (Claes et al., 2014; Ruiz-Linares et al., 2014; Lippert et al., 2017).

Mate Choice, Sexual Dimorphism and Selection

Facial phenotypes can influence mate choice and be under selection pressures. These factors can then affect reproductive behavior and lead to population-level changes in facial variation as certain facial phenotypes are favored. Previous studies have suggested that facial features such as attractiveness (Little et al., 2001; Fink and Penton-Voak, 2002), hair color (Wilde et al., 2014; Adhikari et al., 2016; Field et al., 2016; Hysi et al., 2018), eye color (Little et al., 2003; Wilde et al., 2014; Field et al., 2016) and skin pigmentation (Jablonski and Chaplin, 2000, 2010; Wilde et al., 2014; Field et al., 2016) may influence mate choice and/or have been under historical selection. Features related to appearance are also often sexually dimorphic, possibly as a result of sexual and natural selection. For example, significantly more women self-report having blonde and red hair while more men as self-report as having black hair (Hysi et al., 2018).

The possible evolutionary advantages of facial phenotypes have been discussed extensively but anthropological hypotheses can be tested using genetic and facial phenotype data. For example, a masculine face has been hypothesized to be a predictor of immunocompetence (Scott et al., 2013). A previous study tested this hypothesis using 3D facial images and genetic variation in the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) region and found weak evidence to support this (Zaidi et al., 2018). Other possible benefits that have been explored include: the fitness advantages of hair color (Adhikari et al., 2016; Hysi et al., 2018), nasal shape and climate adaptation (Zaidi et al., 2017) and the benefits of darker skin pigmentation (Wilde et al., 2014; Aelion et al., 2016). Strong levels of phenotypic and genotypic spousal assortment have been previously demonstrated for height (Robinson et al., 2017) and similar methods could be applied using facial phenotypes to explore the influences of facial morphology on mate choice.

So will the incel genome dies out?

one thing is for sure; we won't live long enough to find out