barcacel

Vitantiheterodroidsexual Monk-mode MGTOW

-

- Joined

- Oct 16, 2022

- Posts

- 1,906

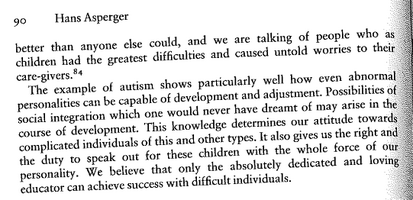

so basicallt the nazi Hans Asperger created this term called "autistic psychopathy" which referred to the children to who we used to diagnose with asperger's syndrome and are now referred as autistic (level 1 autism or high functioning autism), many people believe that he wanted to kill all the kids with autism but that wrong, he believed the kids with autistic psychopathy were superior to normal kids in some aspects, the nazis only wanted to kill the kids with level 2 autism, which is an autism type that is very different to autistic psychopathy (people like chis chan have autism level 2, search it on youtube), the nazis actually believed the children with autistic psychopathy should not be killed:

hitler also was an autistic psychopath and had asperger's like me and all the other users on this forum:

incels.is

incels.is

i will be adding more information to this thread when i'm done researching, there is more information in that book but i'm just reading some parts that had the words "autistic psychopath" through the word finder, i will see if i find more but i will miss many things

these are quotes from the book Asperger’s Children: The Origins of Autism in Nazi Vienna

here is a pdf of the book:

www.pdfdrive.com

www.pdfdrive.com

"Asperger’s definition of autistic psychopathy reflected his admiration of Fritz’s and Harro’s family backgrounds. He asserted, as in Fritz’s case, “Many of the fathers of our autistic children occupy high positions.” As in Harro’s case, “if one happens to find a manual worker among them, then it is probably someone who has missed his vocation.” To Asperger, autistic psychopathy might, in fact, be a result of higher-class breeding. He held, “In many cases the ancestors of these children have been intellectuals for several generations,” and are even from “important artistic and scholarly families.” In autistic youths, Asperger claimed, “sometimes it seems as if of [their ancestors’] former grandeur only the eccentricity remains.” Given these descriptions, one wonders if what was called “eccentricity” in an upperclass child might be deemed a character failing or mental illness in workingclass children such as Elfriede or Margarete." (page 137)

"For Asperger, autistic psychopathy was abstract thinking par excellence. “Abstraction is so highly developed that the relationship to the concrete, to objects and to people has largely been lost" It was boys who had the capability of higher-order thinking. Boys, Asperger contended, had “a gift for logical ability, abstraction, precise thinking and formulating, and for independent scientific investigation,” while girls were suited “for the concrete and the practical, and for tidy, methodical work.” (page 148)

"But while the girls displayed similar behaviors as Fritz and Harro, Asperger’s clinic interpreted only the boys’ idiosyncrasies as signs of superior intelligence. Atypical speech, for example, signaled exceptional capabilities in what Asperger called “favorable cases” of autistic psychopathy. Autistic children had “a special creative attitude towards language,” Asperger wrote. They could “express their own original experience in a linguistically original form.” Though “often quite abstruse,” Asperger held that autistic children’s “newly formed or partially restructured expressions” showed unique insight. When Asperger asked Fritz on his intelligence test the difference between a fly and a butterfly, he was delighted to hear Fritz say: “The butterfly is snowed, snowed with snow,” and “He is red and blue, and the fly is brown and black,’ ” as these seemed refreshingly creative answers. Asperger also praised how Harro “coined each word to fit the moment.” When asked the difference between a stove and an oven, Harro said that “the stove is what one has in the room as a firebringer.” Such use of “unusual words,” Asperger declared, was an “example of autistic introspection.” (page 149)

"Asperger deemed the boys’ refinement genuin. He celebrated how six-yearold Fritz talked ‘like an adult,’ ” and how one could talk to eight-year-old Harro “as to an adult.” Even Ernst, who Asperger believed was more disabled, spoke “like an adult.” The boys also demonstrated autistic intelligence by talking at length about subjects of their own interest, without much regard for the conversational partner. Asperger wrote of Fritz that “Only rarely was what he said in answer to a question,” and that Harro “did not respond to questions but let his talk run single-mindedly along his own tracks.” Ernst, too, talked “regardless of the questions he was being asked,” but his “ ‘asides’ were quite remarkable.” The Curative Education Clinic judged Margarete’s digressive speaking, however, an inadequacy: “She gives roundabout, lengthy accounts” and “never comes to the end.” Rather than a sign of intelligence, this showed “her uncritical, uncontrolled way of thinking.” Margarete was flighty—while the boys showed acuity. That Asperger paid so much attention to the boys’ intelligence is all the more notable given how difficult it was to measure. Despite resistance from the boys, Asperger invested a great deal of effort into proving their capabilities. “Testing was extremely difficult to carry out” with Fritz, for example. He “constantly jumped up or smacked the experimenter on the hand,” and “would repeatedly drop himself from chair to floor and then enjoy being firmly placed back in his chair again.” When presented with the Lazar system of testing that was traditional at the clinic, Fritz refused to imitate rhythms beaten out; he balked at math calculation problems. When asked about the difference between a tree and a bush, he answered only “there is a difference.” When asked the difference between a cow and calf, he returned, “lammerlammerlammer. . . .” Yet Asperger was willing to impute skills to Fritz that he did not demonstrate in the testing. When Fritz repeated up to six digits from memory, Asperger remarked, “One was left with a strong impression that he could go further, except that he just did not feel like it.” Asperger based his claim that Fritz had “extraordinary calculating ability” on discussions with the boy’s parents and, later, individualized instruction in the ward. Fritz’s skills would not have been revealed without the intensive efforts of Asperger and his colleagues to uncover it. Testing Harro was just as difficult as testing Fritz, Asperger held. “A lot of energy went into simply making him do the tasks,” since Harro would “shut off completely when a question did not interest him.” But Asperger, as with Fritz, gave the boy the benefit of the doubt. He deemed Harro’s unusual answers evidence of unusual intelligence. On the difference between a lake and a river, Harro explained: “Well, the lake, it doesn’t move from its spot, and it can never be as long and never have that many branches, and it always has an end" (page 149)

"Asperger also proclaimed that autistic boys had unique powers of perception: a “special clear-sightedness” that was “seen only in them,” with special capabilities to “engage in a particular kind of introspection and to be a judge of character.” He maintained that their “psychopathic clarity of vision” was uncanny, almost miraculous. One “distinctive trait” that Asperger highlighted was autistic boys’ “rare maturity of taste in art.” Whereas “normal children” gravitate toward the “pretty picture, with kitschy rose pink and sky blue,” he claimed, autistic children “may have a special understanding of works of art which are difficult even for many adults.” In Asperger’s opinion, they were especially good at “Romanesque sculpture or paintings by Rembrandt.” Asperger gave no evidence for his claims of “special clear-sightedness” in autistic psychopathy. The right or wrongness of his claims notwithstanding, it is doubtful his clinic gave either Elfriede or Margarete an opportunity to judge either Rembrandt paintings or Romanesque sculptures." (page 151)

"in the conclusion to his treatise, Asperger argued that children with autistic psychopathy could be valuable to society. “Autistic people have their place in the organism of the social community,” he declared, and “they fulfill their role well, perhaps better than anyone else could.” He also defended children with developmental differences in general, contending that “Abnormal personalities can be capable of development and adjustment,” and that “Possibilities of social integration which one would never have dreamt of arise in the course of development.” (page 153)

"Asperger outlined this in the bluntest terms, charging that people with autistic psychopathy spanned “from the highly original genius, through the weird eccentric who lives in a world of his own and achieves very little, down to the most severe contact-disturbed, automaton-like mentally retarded individual.” Essentially, autistic psychopathy had both positive and negative traits, and one could add up a ledger to determine a child’s value. Asperger held that youths on the “most favorable” end of his “range” might be superior to “normal children.” As adults, they would “perform with such outstanding success that one may even conclude that only such people are capable of certain achievements.” This was “usually in highly specialised academic professions, often in very high positions” such as “mathematicians, technologists, industrial chemists and high-ranking civil servants.” Asperger was stressing traits that were valuable to the Nazi state, and this may have been a strategic attempt to defend these children from persecution. But he also attributed some traits to autistic children—such as artistic taste in Rembrandt paintings and Romanesque sculpture—which were rather unusual to spotlight if he did not believe in them." (page 154)

here is a pdf of the book:

Asperger’s Children: The Origins of Autism in Nazi Vienna by Edith Sheffer - PDF Drive

A groundbreaking exploration of the chilling history behind an increasingly common diagnosis. Hans Asperger, the pioneer of autism and Asperger syndrome in Nazi Vienna, has been celebrated for his compassionate defense of children with disabilities. But in this groundbreaking book, prize-winning his

"Asperger’s definition of autistic psychopathy reflected his admiration of Fritz’s and Harro’s family backgrounds. He asserted, as in Fritz’s case, “Many of the fathers of our autistic children occupy high positions.” As in Harro’s case, “if one happens to find a manual worker among them, then it is probably someone who has missed his vocation.” To Asperger, autistic psychopathy might, in fact, be a result of higher-class breeding. He held, “In many cases the ancestors of these children have been intellectuals for several generations,” and are even from “important artistic and scholarly families.” In autistic youths, Asperger claimed, “sometimes it seems as if of [their ancestors’] former grandeur only the eccentricity remains.” Given these descriptions, one wonders if what was called “eccentricity” in an upperclass child might be deemed a character failing or mental illness in workingclass children such as Elfriede or Margarete." (page 137)

"For Asperger, autistic psychopathy was abstract thinking par excellence. “Abstraction is so highly developed that the relationship to the concrete, to objects and to people has largely been lost" It was boys who had the capability of higher-order thinking. Boys, Asperger contended, had “a gift for logical ability, abstraction, precise thinking and formulating, and for independent scientific investigation,” while girls were suited “for the concrete and the practical, and for tidy, methodical work.” (page 148)

"But while the girls displayed similar behaviors as Fritz and Harro, Asperger’s clinic interpreted only the boys’ idiosyncrasies as signs of superior intelligence. Atypical speech, for example, signaled exceptional capabilities in what Asperger called “favorable cases” of autistic psychopathy. Autistic children had “a special creative attitude towards language,” Asperger wrote. They could “express their own original experience in a linguistically original form.” Though “often quite abstruse,” Asperger held that autistic children’s “newly formed or partially restructured expressions” showed unique insight. When Asperger asked Fritz on his intelligence test the difference between a fly and a butterfly, he was delighted to hear Fritz say: “The butterfly is snowed, snowed with snow,” and “He is red and blue, and the fly is brown and black,’ ” as these seemed refreshingly creative answers. Asperger also praised how Harro “coined each word to fit the moment.” When asked the difference between a stove and an oven, Harro said that “the stove is what one has in the room as a firebringer.” Such use of “unusual words,” Asperger declared, was an “example of autistic introspection.” (page 149)

"Asperger deemed the boys’ refinement genuin. He celebrated how six-yearold Fritz talked ‘like an adult,’ ” and how one could talk to eight-year-old Harro “as to an adult.” Even Ernst, who Asperger believed was more disabled, spoke “like an adult.” The boys also demonstrated autistic intelligence by talking at length about subjects of their own interest, without much regard for the conversational partner. Asperger wrote of Fritz that “Only rarely was what he said in answer to a question,” and that Harro “did not respond to questions but let his talk run single-mindedly along his own tracks.” Ernst, too, talked “regardless of the questions he was being asked,” but his “ ‘asides’ were quite remarkable.” The Curative Education Clinic judged Margarete’s digressive speaking, however, an inadequacy: “She gives roundabout, lengthy accounts” and “never comes to the end.” Rather than a sign of intelligence, this showed “her uncritical, uncontrolled way of thinking.” Margarete was flighty—while the boys showed acuity. That Asperger paid so much attention to the boys’ intelligence is all the more notable given how difficult it was to measure. Despite resistance from the boys, Asperger invested a great deal of effort into proving their capabilities. “Testing was extremely difficult to carry out” with Fritz, for example. He “constantly jumped up or smacked the experimenter on the hand,” and “would repeatedly drop himself from chair to floor and then enjoy being firmly placed back in his chair again.” When presented with the Lazar system of testing that was traditional at the clinic, Fritz refused to imitate rhythms beaten out; he balked at math calculation problems. When asked about the difference between a tree and a bush, he answered only “there is a difference.” When asked the difference between a cow and calf, he returned, “lammerlammerlammer. . . .” Yet Asperger was willing to impute skills to Fritz that he did not demonstrate in the testing. When Fritz repeated up to six digits from memory, Asperger remarked, “One was left with a strong impression that he could go further, except that he just did not feel like it.” Asperger based his claim that Fritz had “extraordinary calculating ability” on discussions with the boy’s parents and, later, individualized instruction in the ward. Fritz’s skills would not have been revealed without the intensive efforts of Asperger and his colleagues to uncover it. Testing Harro was just as difficult as testing Fritz, Asperger held. “A lot of energy went into simply making him do the tasks,” since Harro would “shut off completely when a question did not interest him.” But Asperger, as with Fritz, gave the boy the benefit of the doubt. He deemed Harro’s unusual answers evidence of unusual intelligence. On the difference between a lake and a river, Harro explained: “Well, the lake, it doesn’t move from its spot, and it can never be as long and never have that many branches, and it always has an end" (page 149)

"Asperger also proclaimed that autistic boys had unique powers of perception: a “special clear-sightedness” that was “seen only in them,” with special capabilities to “engage in a particular kind of introspection and to be a judge of character.” He maintained that their “psychopathic clarity of vision” was uncanny, almost miraculous. One “distinctive trait” that Asperger highlighted was autistic boys’ “rare maturity of taste in art.” Whereas “normal children” gravitate toward the “pretty picture, with kitschy rose pink and sky blue,” he claimed, autistic children “may have a special understanding of works of art which are difficult even for many adults.” In Asperger’s opinion, they were especially good at “Romanesque sculpture or paintings by Rembrandt.” Asperger gave no evidence for his claims of “special clear-sightedness” in autistic psychopathy. The right or wrongness of his claims notwithstanding, it is doubtful his clinic gave either Elfriede or Margarete an opportunity to judge either Rembrandt paintings or Romanesque sculptures." (page 151)

"in the conclusion to his treatise, Asperger argued that children with autistic psychopathy could be valuable to society. “Autistic people have their place in the organism of the social community,” he declared, and “they fulfill their role well, perhaps better than anyone else could.” He also defended children with developmental differences in general, contending that “Abnormal personalities can be capable of development and adjustment,” and that “Possibilities of social integration which one would never have dreamt of arise in the course of development.” (page 153)

"Asperger outlined this in the bluntest terms, charging that people with autistic psychopathy spanned “from the highly original genius, through the weird eccentric who lives in a world of his own and achieves very little, down to the most severe contact-disturbed, automaton-like mentally retarded individual.” Essentially, autistic psychopathy had both positive and negative traits, and one could add up a ledger to determine a child’s value. Asperger held that youths on the “most favorable” end of his “range” might be superior to “normal children.” As adults, they would “perform with such outstanding success that one may even conclude that only such people are capable of certain achievements.” This was “usually in highly specialised academic professions, often in very high positions” such as “mathematicians, technologists, industrial chemists and high-ranking civil servants.” Asperger was stressing traits that were valuable to the Nazi state, and this may have been a strategic attempt to defend these children from persecution. But he also attributed some traits to autistic children—such as artistic taste in Rembrandt paintings and Romanesque sculpture—which were rather unusual to spotlight if he did not believe in them." (page 154)

hitler also was an autistic psychopath and had asperger's like me and all the other users on this forum:

why the nazis will take over the world, why hitler had autism like us and why 100 percent of children in the US will have autism by 2030

as you know all people on 4chan, incels.is and looksmax.org have autism because of our high neuroticism (high neuroticism is caused by autism)(i have autism), that is why we are so racist, misogynist and we are so different from normies, i can show you hundreds of posts of users of these...

incels.is

incels.is

i will be adding more information to this thread when i'm done researching, there is more information in that book but i'm just reading some parts that had the words "autistic psychopath" through the word finder, i will see if i find more but i will miss many things

Last edited: