PPEcel

cope and seethe

★★★★★

- Joined

- Oct 1, 2018

- Posts

- 29,087

For Americans, who account for almost half of all incels.is members, the First Amendment's protection of freedom of expression is virtually unmatched by any other liberal democracy in a time where rabid online mobs seek to censor or even physically harm incels.

Non-burgercels have a stake as well: while the First Amendment doesn't protect speech in their home countries, the United States' vast influence over the internet still significantly impacts the quality of the content they view online. Indeed, the UK's Independent Reviewer of Terrorism Legislation, Jonathan Hall QC, noted in his most recent report that powerful free speech protections in the United States are difficult for authorities who seek to disrupt "extremist" content (see Conway, 2020).

After three years in the incel community, it's apparent that many of our most vituperative critics are clueless as to what does, and doesn't, constitute protected speech.

Let's get started.

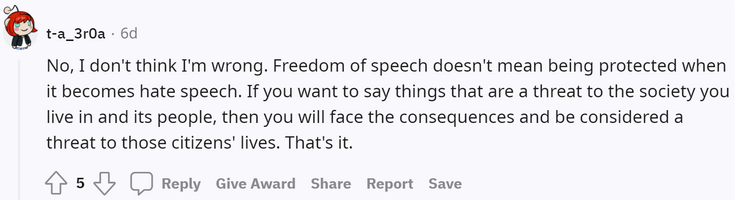

1. "Freedom of speech doesn't mean freedom from consequences."

This is intellectually empty rhetoric. Indeed, a favourite quote of brutal Ugandan despot Idi Amin shares a similar sentiment: "There is freedom of speech, but I cannot guarantee freedom after speech." If Redditors were intellectually honest, they would simply argue, "Well, I just don't believe in freedom of expression as a concept," instead of arguing that imposing arbitrary and ominous consequences on innocent incels who choose to exercise their rights wouldn't violate those same rights.

2. "The First Amendment doesn't protect ISIS, so it shouldn't protect Neo-Nazis or incels either."

Whilst an ISIS member who knowingly provided material support or resources (personnel including oneself) to a designated foreign terrorist organization would likely be prosecuted under 18 U.S.C. § 2339B, the operative words are designated foreign terrorist organization. Notably, 18 U.S.C. § 2339B is one of few laws which have survived a First Amendment challenge on the basis of strict scrutiny, in Holder v. Humanitarian Law Project (2010).

Notwithstanding, the federal judiciary would almost immediately strike down any law to create a register of domestic terrorist organizations akin to that the current list of foreign terrorist organizations, on the basis of the First, Fifth, and Fourteenth Amendments. It wouldn't even be close...not that incels are a legal entity.

3. "Fighting words aren't free speech."

Nothing that an incel could say online could possibly constitute fighting words under the First Amendment.

The fighting words doctrine was established in Chaplinsky v. New Hampshire (1942) to address face-to-face insults that were likely to incite an immediate breach of the peace. Even so, over the past 79 years, the Supreme Court and the federal appeals courts have narrowed Chaplinsky to such an extent some legal scholars question whether such an exception to the First Amendment still exists. In R.A.V. v. City of St. Paul (1992), the Court noted that laws proscribing fighting words do not pass constitutional muster if said laws engage in viewpoint discrimination.

4. "Advocating or inciting violence and threats aren't free speech."

Before we proceed, it is important to distinguish between the colloquial understanding of the term incitement and the constitutionally proscribable incitement to imminent lawless action, as is understood by the legal community. The mere advocacy of violence is protected by the First Amendment. Saying "Every Stacy deserves to be raped and decapitated," is distasteful, but protected. Incitement is only proscribable if it is likely to culminate in illegal action imminently, not at some indefinite future time.

I have previously written in far greater detail regarding the legal history of the advocacy of violence as well as the "true threats" exception to the First Amendment. The vast majority of incel speech simply does not fall under either of these narrowly defined exceptions.

5. "The clear and present danger test allows the government to censor incel speech, by balancing free speech and X."

The Clear and Present Danger test, first articulated in Schenck v. United States (1919), has been overturned for over well over half a century by Brandenburg v. Ohio (1969). Schenck was a case in which the U.S. government sought to charge with sedition a man who distributed anti-war leaflets and is now widely regarded as a bad decision. Yet normies continue to misquote Oliver Wendell Holmes; something about "(falsely) shouting fire in a crowded theatre..."

A similar line of thought popular among Redditors suggests that free speech is a balancing act and can be proscribed for the purposes of other governmental interests, such as social justice.

Here, the Courts strongly disagree: First Amendment jurisprudence holds that speech is unprotected only if it falls into one of narrow, predefined exceptions; it is not the domain of the judiciary to "balance" freedom of speech with X, Y, or Z. In an 8-1 ruling holding that depictions of animal cruelty are not categorically unprotected by the First Amendment, Chief Justice Roberts wrote in United States v. Stevens (2010):

6. "Hate speech is not free speech."

Hate speech is free speech. There is no hate speech exception to the First Amendment. Period. Viewpoint discrimination, as opposed to content-neutral regulation, is presumptively unconstitutional.

The Supreme Court most recently considered this question in its unanimous decision in Matal v. Tam (2017):

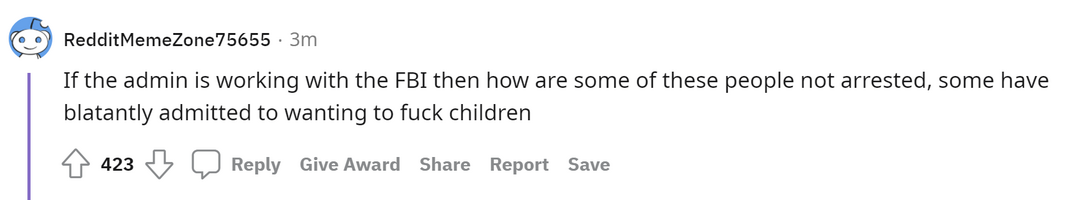

7. "Free speech doesn't protect the glorification of rape or pedophilia."

The mere expression of sexual interest in children and young teenagers in general, while extremely distasteful, is not criminal.

On an indirectly related note, in Ashcroft v. Free Speech Coalition (2002), the Supreme Court struck down two provisions of the Child Pornography Prevention Act of 1996, holding that simulated child pornography was not necessarily unprotected by the First Amendment. Justice Kennedy wrote for a 6-3 majority:

In addition, multiple federal appeals courts have ruled that paedophilia by itself does not constitute probable cause to search for child pornography (though I digress from the topic because this is a Fourth Amendment issue, not a First Amendment one). In United States v. Falso (2008), the Second Circuit noted that:

8. "Muh stochastic terrorists!"

"Stochastic terrorism" is a pretty trendy term lately amongst pundits. In essence, "stochastic terrorism" describes speech that invites hatred against certain individuals or groups, causing listeners to engage in violence, even though said speech does not explicitly incite terrorism. "Stochastic" refers to the element of randomness in the indirectly causal relationship between the speaker and a violent listener.

The concept of "stochastic terrorism" has no legal construction, not in the United States, in fact not anywhere.

Like hate speech, what Redditors describe as "stochastic terrorism" is free speech.

9. "Free speech was intended to only allow speech criticizing the government."

Ah, right. Well, now that we're adopting some bastardized version of originalism that would make even Scalia look like a liberal by comparison, the right to vote was meant only for white, land-owning men, it was never meant for femoids.

10. "Speech can be intolerant. Karl Popper's paradox of tolerance permits us to deny free speech to the intolerant."

Whilst not specific to the First Amendment, it is not uncommon to notice left-wing authoritarians justify violence under the guise of Karl Popper's paradox of tolerance. The following is oft taken out of context from his book, the Open Society and its Enemies:

Less quoted is Karl Popper's next sentence, which does not give the warrant to suppress "intolerance" as the SJWs think it does:

John Rawls questions in his 1971 magnum opus, A Theory of Justice, whether intolerating intolerance would make society itself intolerant, and therefore unjust. My question is more straightforward: who gets to decide what constitutes intolerance?

Non-burgercels have a stake as well: while the First Amendment doesn't protect speech in their home countries, the United States' vast influence over the internet still significantly impacts the quality of the content they view online. Indeed, the UK's Independent Reviewer of Terrorism Legislation, Jonathan Hall QC, noted in his most recent report that powerful free speech protections in the United States are difficult for authorities who seek to disrupt "extremist" content (see Conway, 2020).

After three years in the incel community, it's apparent that many of our most vituperative critics are clueless as to what does, and doesn't, constitute protected speech.

Let's get started.

1. "Freedom of speech doesn't mean freedom from consequences."

This is intellectually empty rhetoric. Indeed, a favourite quote of brutal Ugandan despot Idi Amin shares a similar sentiment: "There is freedom of speech, but I cannot guarantee freedom after speech." If Redditors were intellectually honest, they would simply argue, "Well, I just don't believe in freedom of expression as a concept," instead of arguing that imposing arbitrary and ominous consequences on innocent incels who choose to exercise their rights wouldn't violate those same rights.

2. "The First Amendment doesn't protect ISIS, so it shouldn't protect Neo-Nazis or incels either."

Whilst an ISIS member who knowingly provided material support or resources (personnel including oneself) to a designated foreign terrorist organization would likely be prosecuted under 18 U.S.C. § 2339B, the operative words are designated foreign terrorist organization. Notably, 18 U.S.C. § 2339B is one of few laws which have survived a First Amendment challenge on the basis of strict scrutiny, in Holder v. Humanitarian Law Project (2010).

Notwithstanding, the federal judiciary would almost immediately strike down any law to create a register of domestic terrorist organizations akin to that the current list of foreign terrorist organizations, on the basis of the First, Fifth, and Fourteenth Amendments. It wouldn't even be close...not that incels are a legal entity.

3. "Fighting words aren't free speech."

Nothing that an incel could say online could possibly constitute fighting words under the First Amendment.

The fighting words doctrine was established in Chaplinsky v. New Hampshire (1942) to address face-to-face insults that were likely to incite an immediate breach of the peace. Even so, over the past 79 years, the Supreme Court and the federal appeals courts have narrowed Chaplinsky to such an extent some legal scholars question whether such an exception to the First Amendment still exists. In R.A.V. v. City of St. Paul (1992), the Court noted that laws proscribing fighting words do not pass constitutional muster if said laws engage in viewpoint discrimination.

4. "Advocating or inciting violence and threats aren't free speech."

Before we proceed, it is important to distinguish between the colloquial understanding of the term incitement and the constitutionally proscribable incitement to imminent lawless action, as is understood by the legal community. The mere advocacy of violence is protected by the First Amendment. Saying "Every Stacy deserves to be raped and decapitated," is distasteful, but protected. Incitement is only proscribable if it is likely to culminate in illegal action imminently, not at some indefinite future time.

I have previously written in far greater detail regarding the legal history of the advocacy of violence as well as the "true threats" exception to the First Amendment. The vast majority of incel speech simply does not fall under either of these narrowly defined exceptions.

5. "The clear and present danger test allows the government to censor incel speech, by balancing free speech and X."

The Clear and Present Danger test, first articulated in Schenck v. United States (1919), has been overturned for over well over half a century by Brandenburg v. Ohio (1969). Schenck was a case in which the U.S. government sought to charge with sedition a man who distributed anti-war leaflets and is now widely regarded as a bad decision. Yet normies continue to misquote Oliver Wendell Holmes; something about "(falsely) shouting fire in a crowded theatre..."

A similar line of thought popular among Redditors suggests that free speech is a balancing act and can be proscribed for the purposes of other governmental interests, such as social justice.

Here, the Courts strongly disagree: First Amendment jurisprudence holds that speech is unprotected only if it falls into one of narrow, predefined exceptions; it is not the domain of the judiciary to "balance" freedom of speech with X, Y, or Z. In an 8-1 ruling holding that depictions of animal cruelty are not categorically unprotected by the First Amendment, Chief Justice Roberts wrote in United States v. Stevens (2010):

The First Amendment’s guarantee of free speech does not extend only to categories of speech that survive an ad hoc balancing of relative social costs and benefits. The First Amendment itself reflects a judgment by the American people that the benefits of its restrictions on the Government outweigh the costs.

6. "Hate speech is not free speech."

Hate speech is free speech. There is no hate speech exception to the First Amendment. Period. Viewpoint discrimination, as opposed to content-neutral regulation, is presumptively unconstitutional.

The Supreme Court most recently considered this question in its unanimous decision in Matal v. Tam (2017):

Speech that demeans on the basis of race, ethnicity, gender, religion, age, disability, or any other similar ground is hateful; but the proudest boast of our free speech jurisprudence is that we protect the freedom to express "the thought that we hate."

7. "Free speech doesn't protect the glorification of rape or pedophilia."

The mere expression of sexual interest in children and young teenagers in general, while extremely distasteful, is not criminal.

On an indirectly related note, in Ashcroft v. Free Speech Coalition (2002), the Supreme Court struck down two provisions of the Child Pornography Prevention Act of 1996, holding that simulated child pornography was not necessarily unprotected by the First Amendment. Justice Kennedy wrote for a 6-3 majority:

[the government] may not suppress lawful speech as the means to suppress unlawful speech. Protected speech does not become unprotected merely because it resembles the latter

In addition, multiple federal appeals courts have ruled that paedophilia by itself does not constitute probable cause to search for child pornography (though I digress from the topic because this is a Fourth Amendment issue, not a First Amendment one). In United States v. Falso (2008), the Second Circuit noted that:

It is an inferential fallacy of ancient standing to conclude that, because members of group A (those who collect child pornography) are likely to be members of group B (those attracted to children), then group B is entirely or even largely composed of, members of group A.

8. "Muh stochastic terrorists!"

"Stochastic terrorism" is a pretty trendy term lately amongst pundits. In essence, "stochastic terrorism" describes speech that invites hatred against certain individuals or groups, causing listeners to engage in violence, even though said speech does not explicitly incite terrorism. "Stochastic" refers to the element of randomness in the indirectly causal relationship between the speaker and a violent listener.

The concept of "stochastic terrorism" has no legal construction, not in the United States, in fact not anywhere.

Like hate speech, what Redditors describe as "stochastic terrorism" is free speech.

9. "Free speech was intended to only allow speech criticizing the government."

Ah, right. Well, now that we're adopting some bastardized version of originalism that would make even Scalia look like a liberal by comparison, the right to vote was meant only for white, land-owning men, it was never meant for femoids.

10. "Speech can be intolerant. Karl Popper's paradox of tolerance permits us to deny free speech to the intolerant."

Whilst not specific to the First Amendment, it is not uncommon to notice left-wing authoritarians justify violence under the guise of Karl Popper's paradox of tolerance. The following is oft taken out of context from his book, the Open Society and its Enemies:

Unlimited tolerance must lead to the disappearance of tolerance. If we extend unlimited tolerance even to those who are intolerant, if we are not prepared to defend a tolerant society against the onslaught of the intolerant, then the tolerant will be destroyed, and tolerance with them.

Less quoted is Karl Popper's next sentence, which does not give the warrant to suppress "intolerance" as the SJWs think it does:

In this formulation, I do not imply, for instance, that we should always suppress the utterance of intolerant philosophies; as long as we can counter them by rational argument and keep them in check by public opinion, suppression would certainly be most unwise.

John Rawls questions in his 1971 magnum opus, A Theory of Justice, whether intolerating intolerance would make society itself intolerant, and therefore unjust. My question is more straightforward: who gets to decide what constitutes intolerance?

Last edited: