InMemoriam

Celiacel

★★★★★

- Joined

- Feb 19, 2022

- Posts

- 8,732

RRESEARCH

Facial Attractiveness: Less Important For Male Dateability

- byAlexander

- January 30, 2023

- 3 comments

- 12 minute read

However, scales may not accurately capture how we consider facial attractiveness for dating. While we are able to rate faces on scales if asked, in practice attractiveness may function more like a gate. A person is either below or above our threshold for attractiveness. We make a binary decision. We decide “hot or not” and we “swipe left or swipe right.”

Methodology

I conducted a survey (N = 1,812) using faces from the Chicago Face Database (CFD). Faces in the CFD have been pre-rated for attractiveness by 1,087 raters (Ma & Wittenbrink, 2015).From the CFD, I selected 15 male and 15 female faces that were within a specific window of attractiveness ratings: above a 3 and below a 4. The faces selected were one standard deviation above the pre-rated mean in attractiveness.

I wanted to begin with “above average” faces, but not “attractive” faces. (What is the difference? We will see below.)

Male and female face photos from the CFD are standardized in dress, unedited, and presented against a white background. Faces all had neutral expressions. The average age of selected male and female faces was close (Men = 26.4, SD = 4.6; Women = 26.6, SD = 4.2).

Participants rated opposite-sex faces on two items:

- A binary option that let participants choose: “This person is attractive enough for me to date” or “This person is not attractive enough for me to date.”

- A Likert scale (1-7): “Very Unattractive, Unattractive, Slightly Unattractive, Average, Slightly Attractive, Attractive, Very Attractive.” The item was: “I would describe the previous face as:.”

In the development of the Chicago Face Database, raters were asked a different question when giving ratings of attractiveness:

- “Consider the person pictured above and rate him/her with respect to other people of the same race and gender.”

This is a question about where someone resides in a population. You might expect this to fall on a normal distribution around the midpoint of the scale, but it did not (unsurprising, see: Is Physical Attractiveness Normally Distributed?). Raters indicated that most faces were less attractive than the average person.

In the CFD, the average rating for White men was a 2.98, with a standard deviation of .8. For White women, it was 3.35, with a standard deviation of .66. Very few men or women were rated a 4 or above. This is on a 7 point scale!

You may be thinking that the CFD is a database of unattractive faces. However, many of these faces were recruited from amateur actors and models. In other words, these were people who used their faces in a professional capacity. Now, being an actor or a model does not mean someone is hot — that is a common misconception. It is an activity where looks matter, however, and it does tend to exclude those who are ugly. They need to look good enough to appear on camera, in advertisements, and to sell products.

It may be the case that the CFD is biased toward less attractive faces. Given the selection, I don’t think this is the case. It is implausible that a sample of students, actors, and models should be less attractive than the general population. Given the age of the faces, and the correlation between age and facial attractiveness (He et al., 2021; Jones & Hill, 1993), we should also expect faces in the CFD to be more attractive than “other people of the same race and gender,” which includes the elderly. Being a young demographic alone should shift faces used in the CFD and in the current study to the right of the curve relative to the general population.

Presentation may be a better explanation. People who are otherwise attractive may simply look worse when you don’t let them use makeup (Arai & Nittono, 2022; Osborn, 1996), don’t let them style themselves how they wish (Cunningham et al., 1990), and don’t let them present themselves in their most attractive light (Toma & Hancock, 2010). This may also explain the gender gap in OKCupid ratings.

A third explanation: most people don’t see most people as attractive. Even when asked to rate people “objectively,” we are unable to dissociate our own feelings for a face with what is a “below average” face in a population.

Selection of Faces

As I have written about in the past, an “average” face is not determined by the midpoint of the scale you use. Averageness is a feature of your dataset and is determined by the responses that faces receive. If most faces are “unattractive,” then the average will also fall within what is “unattractive.”

For this survey, I selected faces that were between a 3 and a 4 out of 7. This also means that selected faces were one standard deviation above the mean in the CFD. Again, this is why we can’t confuse “above average” faces with “attractive” faces — “attractive” faces would have been in the top 10% of the CFD!

In summary, there are two ways to interpret the faces selected as stimuli in this survey and both are correct:

- Faces that received mathematically above-average ratings.

- Faces that were pre-rated as a 3 out of 7, relative to the population.

Results

Descriptive statistics335 participants were female, 1439 were male, and 13 reported as other gender. 85.5% of respondents reported as heterosexual, 11.7% as bisexual, 2% as homosexual, and 0.8% as other. The average age for men was 30.6 (median 27, SD 7.87) and for women was 28.5 (median 27, 9.70).

Facial Ratings

Facial rating scores passed the Shapiro-Wilk normality check and t-tests were performed for mean ratings. Men and women did not rate opposite sex faces differently on a 1-7 Likert scale of attractiveness (t(27) = 1.92, p = 0.649). Mean ratings for faces given by the current sample were not significantly different from CFD pre-ratings of men or women (Male faces, t(21) = 1.92, p = 0.068; Female faces, t(22) = -0.63, p = 0.536). CFD pre-ratings for male and female faces were also not significantly different (t(27) = 0.21, p = 0.839).

Cronbach’s alpha was high for raters (Male, α = .9; Female, α = .89). Intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC) showed good reliability for male (.88, 95% CI [.85, .89]) and female (.85, 95% CI [.82, .87]) raters. ICC for single random raters was slightly higher for male raters (.32, 95% CI [.28, .36]) than for female raters (.27, 95% CI [.23, .32]).

Table 1 shows means and standard deviations for participant ratings and for CFD pre-ratings, as well as the number of faces rated “average,” or above a 4, in participant ratings.

Who Was Dateable

Men and women differed in their responses of who was dateable, with women indicating more willingness to date the men they saw in the photos (X²(1, N = 1,812) = 87, p < .001).

More women than men were also willing to date both the most and least attractive faces.

Table 2 shows the mean percentage of participants indicating a willingness to date the faces they saw, as well as the range of participants willing to date the most and least attractive faces. In both male and female face categories, three faces were rated as dateable by more than 50% of opposite-sex participants.

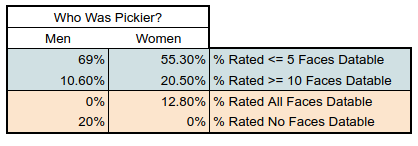

I also looked at how individual men and women rated faces to ask: who is “pickier.” Picker individuals should have fewer faces they are willing to date.

Less picky individuals should have more faces they are willing to date.

Women were more willing to date the least attractive five faces than men (X²(1, N = 1,812) = 69, p < .001). Men rated fewer faces dateable than women, with 69% of men rating five or fewer faces dateable and 55% of women rating five or fewer faces dateable. More women than men also rated ten or more faces dateable — about twice as many women.

Additionally, not one single man (out of the entire 1,439) rated all 15 faces as dateable. Meanwhile, not one single woman rated every male face as undateable (Table 3).

Table 4 shows the percentages of men and women that were willing to date the five least attractive faces. Women were more willing to date unattractive men than men were willing to date unattractive women.

Women also rated the least attractive men higher than men rated the least attractive women (t(7) = 3.42, p = 0.011).

Facial attractiveness was moderately correlated with dateability, but the magnitude of the correlation was similar for men (r = .634, p < .001) and women (r = .612, p < .001).

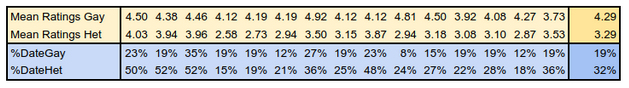

Gay and Bisexual Men

Gay men gave higher Likert ratings of attractiveness to women than heterosexual men (t(24) = 6.71, p < 0.001) and bisexual men (t(22) = 4.58, p < 0.001). Bisexual men did not rate female faces differently from heterosexual men (t(27) = 1.43, p = 0.161). Only two of fifteen faces were rated below a four by gay men. Only one female face was rated a four by heterosexual men.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, this difference was not replicated when asked about willingness to date. Gay men were less willing to date the women in photos than heterosexual men (Table 5).

Age

Age was a weak positive predictor of male ratings for female faces (r = .156, p < .001) and male willingness to date (r = 0.61, p = .02). Willingness to date would not survive correction for multiple comparisons. There was no relationship with age and female ratings of faces (r = .088, p = .108), and no relationship with age and female willingness to date male faces (r = .084, p = .124).

Discussion

People have speculated on the OKCupid dataset (Figure 1) that men rate women according to the mathematical average, while women rate men according to their subjective feelings. This is based on the assumption that attractiveness is normally distributed and that male ratings resemble a normal distribution more.

The current results indicate that men and women don’t express systematic differences in facial rating strategies. Men and women did not rate opposite-sex faces that were pre-selected to be equally attractive and normally distributed differently.

Differences in rating distributions, such as those found within more naturalistic datasets (uncontrolled photos on dating apps), are more likely to be a feature of those photos than of differences in rating strategies between men and women.

Differences may also be due to sex differences in attractiveness between men and women in the general population, differences in presentation style (such as the use of makeup), or due to differences found in dating app populations.

Further, the phrasing of the question did not influence ratings. Men and women in the current study rated faces that they felt were subjectively attractive similarly to how CFD pre-raters rated faces when asked to rate them relative to the population.

It may be that we don’t internally dissociate our own feelings about a face when asked to rate it, even when explicitly asked to consider it in a more objective way.

The CFD also used a sample of mixed-gender raters. Consistent results from mixed ratings and opposite-sex ratings in two large samples of raters further indicates that men and women don’t express different strategies for rating faces. Past research has also found that men and women rate faces similarly (Marcus & Miller, 2003).

Convenience Samples

The current results are consistent with past research on facial attractiveness that has found ratings are shared across disparate samples of raters (Langlois et al., 2000). Indeed, in the current results we see high inter-rater agreement, as well as high agreement across two different convenience samples.

Approximately 90% of samples in psychology use convenience samples (Jager et al., 2017) and this has raised questions about generalizability.

However, past research has found that within some disciplines in psychology, generalizability from convenience samples to the general population is high (Vitriol et al., 2019; Coppock et al., 2018). This may be the case for research on facial attractiveness using convenience samples as well.

Willingness To Date

Men and women did express different strategies when asked about attractiveness sufficient for dateability. Women were less discriminating than men when it came to facial attractiveness. This might be surprising for those with Tinder brain, but it is consistent with past research in evolutionary psychology, which has consistently found that men prioritize physical attractiveness more than women do in partner selection (Buss, 1989; Meltzer et al., 2014).

This should not be interpreted as women being less selective overall. There is good reason to believe women are more selective than men (see Buss & Schmitt, 2017 for review). However, this selectivity is expressed across a range of behavioral traits and may rely less on physical attractiveness than it does for men. Thus, when facial attractiveness is the only variable considered we may see men emerge as more selective on the basis of that measurement.

Most People Are Unattractive to Most People

There is a small cohort of people who are attractive to most people. They become actors, models, and influencers. If it frustrates you that you are not in this cohort you may have unrealistic expectations for yourself and for the world around you. Even the Gigachad is not attractive to most women (see: Women Don’t Find Gigachad Attractive).

Despite being young students, models, and actors, the faces in the CFD don’t seem to be from this facially elite cohort. Even faces that are mathematically above average in ratings were not dateable to most people. If we recall that more people in the database fall to the left of the selected faces than to the right, we can conclude that most people are not attractive enough to be dateable to most people.

However, this is not as bleak as it sounds.

Most People Are Dateable To Enough People

There is good news buried in this data. The least attractive male face was still dateable to 25% of women. The least attractive female face was dateable to 15% of men. These two faces were rated a 3 and a 2, respectively, so even at the lower end of subjective attractiveness the doors to a romantic relationship are not barred.

Failure to dissociate ratings of facial attractiveness from dateability may also lead to the erroneous conclusion that most people are not desirable. However, individual variability in selection means that some people really do find “unattractive” faces to be attractive and that ratings for individual faces can have high variation (Hönekopp, 2006). Intraclass correlations for single raters was low in the current results, despite mean agreement being high. In this sample, 11.5% of women found the most unattractive face to be above average in attractiveness.

That is already good news — because you only need one person to find you attractive — but it gets better when you consider that dateability was even higher than attractiveness ratings might imply.

References

Arai, T., & Nittono, H. (2022). Cosmetic makeup enhances facial attractiveness and affective neural responses. Plos one, 17(8), e0272923.Buss, D. M. (1989). Sex differences in human mate preferences: Evolutionary hypotheses tested in 37 cultures. Behavioral and brain sciences, 12(1), 1-14.

Buss, D. M., & Schmitt, D. P. (2017). Sexual strategies theory: An evolutionary perspective on human mating. In Interpersonal Development (pp. 297-325). Routledge.

Cunningham, M. R., Barbee, A. P., & Pike, C. L. (1990). What do women want? Facialmetric assessment of multiple motives in the perception of male facial physical attractiveness. Journal of personality and social psychology, 59(1), 61.

Coppock, A., Leeper, T. J., & Mullinix, K. J. (2018). Generalizability of heterogeneous treatment effect estimates across samples. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 115(49), 12441-12446.

He, D., Workman, C. I., Kenett, Y. N., He, X., & Chatterjee, A. (2021). The effect of aging on facial attractiveness: An empirical and computational investigation. Acta psychologica, 219, 103385.

Hönekopp, J. (2006). Once more: is beauty in the eye of the beholder? Relative contributions of private and shared taste to judgments of facial attractiveness. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 32(2), 199.

Jager, J., Putnick, D. L., & Bornstein, M. H. (2017). II. More than just convenient: The scientific merits of homogeneous convenience samples. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 82(2), 13-30.

Jones, D., & Hill, K. (1993). Criteria of facial attractiveness in five populations. Human Nature, 4(3), 271-296.

Langlois, J. H., Kalakanis, L., Rubenstein, A. J., Larson, A., Hallam, M., & Smoot, M. (2000). Maxims or myths of beauty? A meta-analytic and theoretical review. Psychological bulletin, 126(3), 390.

Ma, D. S., Correll, J., & Wittenbrink, B. (2015). The Chicago face database: A free stimulus set of faces and norming data. Behavior research methods, 47(4), 1122-1135.

Marcus, D. K., & Miller, R. S. (2003). Sex differences in judgments of physical attractiveness: A social relations analysis. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 29(3), 325-335.

Meltzer, A. L., McNulty, J. K., Jackson, G. L., & Karney, B. R. (2014). Sex differences in the implications of partner physical attractiveness for the trajectory of marital satisfaction. Journal of personality and social psychology, 106(3), 418.

Osborn, D. R. (1996). Beauty is as beauty does?: Makeup and posture effects on physical attractiveness judgments 1. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 26(1), 31-51.

Toma, C. L., & Hancock, J. T. (2010). Looks and lies: The role of physical attractiveness in online dating self-presentation and deception. Communication research, 37(3), 335-351.

Vitriol, J. A., Larsen, E. G., & Ludeke, S. G. (2019). The generalizability of personality effects in politics. European Journal of Personality, 33(6), 631-641.