PPEcel

cope and seethe

-

- Joined

- Oct 1, 2018

- Posts

- 29,087

Despite the oft-repeated and misleading SJW talking point that "freedom of speech doesn't protect one from freedom of consequences," the First Amendment does in fact protect one from consequences imposed by state actors—including public schools. And one thing that American school administrators seem to forget constantly is that students, too, have free speech rights, more so when they’re off-campus.

Last month, officials at the Cherry Creek School District in Colorado learned this the hard way when the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit revived a federal lawsuit filed against the district for violating the First Amendment.

You can read the Tenth Circuit's decision in C1.G. v. Siegfried here.

Related news article for lazycels:

Background

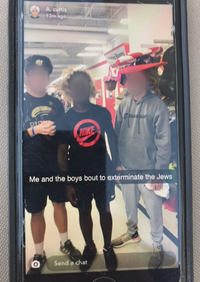

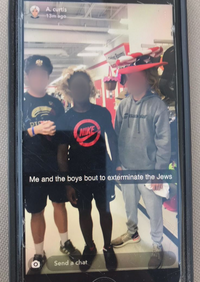

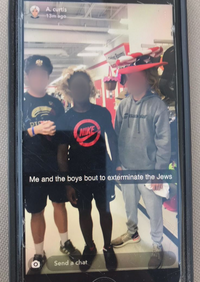

On September 13th, 2019, C.G. was shopping at a thrift store with his friends when they decided to try on costumes and silly hats, including one that resembled a WWII-era military hat. C.G. took a picture of three of his friends and posted it as a Snapchat story, with an accompanying tagline: "Me and the boys bout to exterminate the Jews". Soon after, C.G. deleted the post (see below), realizing that the joke was in bad taste.

But a femoid Snapchat "friend" had already screenshotted the post and notified her parents, who called the police and shared it with other parents. A police officer visited C.G.'s home and determined that there was no threat. Four parents filed a complaint with the school district. C.G. was initially suspended for five days before school officials decided on expulsion.

C.G.'s parents soon filed a federal lawsuit, but the district court dismissed the case in August 2020, which erroneously held that the school's responsibility to prevent disruptions on campus trumped C.G.'s First Amendment rights. C.G.'s parents appealed.

But while C.G.'s case was pending, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled on an unrelated but similar case involving high school students' online speech rights. Brandi Levy (see below) was a high school sophomore in Pennsylvania who was upset about not having been selected for the varsity team. So, after school hours, she went on Snapchat and posted a picture of herself giving the middle finger, with the caption "fuck school fuck softball fuck cheer fuck everything". Levy's coaches found out and kicked her off the junior varsity team. After Levy’s parents sued, a federal judge granted an injunction ordering Levy's high school to reinstate her to the JV cheerleading team. The school district appealed the case all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court, where the Court sided with Levy in an 8-1 ruling.

Justice Stephen Breyer, who authored the majority opinion in Mahanoy Area School District v. B.L., 141 S. Ct. 2038 (2021), declined to specify where exactly schools can regulate off-campus speech without infringing on the First Amendment. Instead, Breyer merely noted that the courts should be "skeptical" of schools' attempts to regulate off-campus speech, that schools must face a "heavy burden" to justify doing so, and that schools themselves have an interest in protecting, not suppressing, unpopular speech: (Id. at 2046)

Justice Samuel Alito agreed with Breyer. In a concurring opinion, Alito noted that allowing schools to punish students merely for unpopular speech would be tantamount to a heckler's veto: "If listeners riot because they find speech offensive, schools should punish the rioters, not the speaker."

The Tenth Circuit's Decision

The Byron White U.S. Courthouse in Denver, CO

In light of the U.S. Supreme Court's decision in Mahanoy, it's unsurprising that free speech advocates and school administrators alike turned their attention to C.G.'s case: both involved high school students using Snapchat outside school hours. No less than four civil rights organizations—the ACLU of Colorado, FIRE, EFF, and the Cato Institute—filed amicus briefs in support of C.G.

Meanwhile, lawyers for the Cherry Creek School District and the National School Boards Association attempted to distinguish C.G.'s online speech from that of Levy's on the basis that it was “uniquely regulable” because it was “hate speech targeting the Jewish community”.

A three-judge panel of the Tenth Circuit unanimously rejected this argument. Judge Paul Joseph Kelly Jr., joined by Judges Scott Matheson Jr. and Carolyn B. McHugh, wrote that C.G.’s off-campus joke about “exterminating the Jews” would “generally receive First Amendment protection because it does not constitute a true threat, fighting words, or obscenity.” In a footnote, Judge Kelly added that “words as mere political argument, idle talk or jest” do not constitute “true threats”, citing United States v. Heineman, 767 F.3d 970, 972-973 (10th Cir. 2014).

“Defendants [the school district] cannot claim a reasonable forecast of substantial disruption to regulate C.G.’s off-campus speech by simply invoking the words “harass” and “hate” when C.G.’s speech does not constitute harassment and its hateful nature is not regulable in this context,” Judge Kelly concluded.

Why this Case Matters

Over the years, schools and public employers alike have expanded their definition of “discrimination” and “bullying” to cover not only violent threats and targeted harassment but also the mere utterance of politically incorrect viewpoints. Most institutions have spinelessly acquiesced to left-wing demands to enforce ideological conformity at the expense of freedom of speech and due process. It was inevitable that the excesses of progressivism would run into constitutional headwinds.

For decades, the judiciary has consistently held that “hate speech” is in fact free speech, even in an educational setting. Since the late 1980s, the federal courts repeatedly have struck down “anti-discrimination” speech codes, much to the chagrin of soys. See e.g., Doe v. University of Michigan, 721 F. Supp. 852 (E.D. Mich.1989); UWM Post v. Board of Regents of University of Wisconsin, 774 F. Supp. 1163 (E.D. Wis. 1991); Bair v. Shippensburg University, 280 F. Supp. 2d. 357 (M.D. Pa. 2003). As recently as 2021, the Sixth Circuit found that a college professor had a First Amendment right to “misgender” his students. Meriwether v. Hartop, 992 F.3d 492 (6th Cir. 2021).

Though C1.G. v. Siegfried considers the off-campus speech rights of high school students writing online (as opposed to the on-campus speech rights of college students and professors), the gist of the decision remains similar: it is not the place of educators to act as the social justice thought police.

All of these precedential First Amendment cases have important implications for American incels. Imagine if a 16-year-old boy was sitting at a cafe or in the town library after school, and a classmate inadvertently noticed his screen activity. Perhaps he was venting on Discord or Reddit or even our forum. “i hate my life all the foids at school are sluts who suck chads cock only” might upset a leftist school administrator, but as it currently stands, the U.S. Constitution bars public schools from disciplining a student for writing such a comment outside school hours.

For us, it’s a positive development that both the U.S. Supreme Court and now the Tenth Circuit have put overzealous school officials on notice: You may face legal consequences for trampling on your students’ constitutionally protected speech, even if a mob of pink-haired soys are triggered by “muh hates peach”.

Keep seething, cucks. These based federal judges have lifetime appointments and will be around for quite a while.

Last month, officials at the Cherry Creek School District in Colorado learned this the hard way when the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit revived a federal lawsuit filed against the district for violating the First Amendment.

You can read the Tenth Circuit's decision in C1.G. v. Siegfried here.

Related news article for lazycels:

Student expelled for offensive Snapchat post can sue school district, 10th Circuit says

The ABA Journal is read by half of the nation's 1 million lawyers every month. It covers the trends, people and finances of the legal profession from Wall Street to Main Street to Pennsylvania Avenue.

www.abajournal.com

Background

On September 13th, 2019, C.G. was shopping at a thrift store with his friends when they decided to try on costumes and silly hats, including one that resembled a WWII-era military hat. C.G. took a picture of three of his friends and posted it as a Snapchat story, with an accompanying tagline: "Me and the boys bout to exterminate the Jews". Soon after, C.G. deleted the post (see below), realizing that the joke was in bad taste.

But a femoid Snapchat "friend" had already screenshotted the post and notified her parents, who called the police and shared it with other parents. A police officer visited C.G.'s home and determined that there was no threat. Four parents filed a complaint with the school district. C.G. was initially suspended for five days before school officials decided on expulsion.

C.G.'s parents soon filed a federal lawsuit, but the district court dismissed the case in August 2020, which erroneously held that the school's responsibility to prevent disruptions on campus trumped C.G.'s First Amendment rights. C.G.'s parents appealed.

But while C.G.'s case was pending, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled on an unrelated but similar case involving high school students' online speech rights. Brandi Levy (see below) was a high school sophomore in Pennsylvania who was upset about not having been selected for the varsity team. So, after school hours, she went on Snapchat and posted a picture of herself giving the middle finger, with the caption "fuck school fuck softball fuck cheer fuck everything". Levy's coaches found out and kicked her off the junior varsity team. After Levy’s parents sued, a federal judge granted an injunction ordering Levy's high school to reinstate her to the JV cheerleading team. The school district appealed the case all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court, where the Court sided with Levy in an 8-1 ruling.

Justice Stephen Breyer, who authored the majority opinion in Mahanoy Area School District v. B.L., 141 S. Ct. 2038 (2021), declined to specify where exactly schools can regulate off-campus speech without infringing on the First Amendment. Instead, Breyer merely noted that the courts should be "skeptical" of schools' attempts to regulate off-campus speech, that schools must face a "heavy burden" to justify doing so, and that schools themselves have an interest in protecting, not suppressing, unpopular speech: (Id. at 2046)

“America’s public schools are the nurseries of democracy. Our representative democracy only works if we protect the “marketplace of ideas.” This free exchange facilitates an informed public opinion, which, when transmitted to lawmakers, helps produce laws that reflect the People’s will. That protection must include the protection of unpopular ideas, for popular ideas have less need for protection.”

Justice Samuel Alito agreed with Breyer. In a concurring opinion, Alito noted that allowing schools to punish students merely for unpopular speech would be tantamount to a heckler's veto: "If listeners riot because they find speech offensive, schools should punish the rioters, not the speaker."

The Tenth Circuit's Decision

The Byron White U.S. Courthouse in Denver, CO

In light of the U.S. Supreme Court's decision in Mahanoy, it's unsurprising that free speech advocates and school administrators alike turned their attention to C.G.'s case: both involved high school students using Snapchat outside school hours. No less than four civil rights organizations—the ACLU of Colorado, FIRE, EFF, and the Cato Institute—filed amicus briefs in support of C.G.

Meanwhile, lawyers for the Cherry Creek School District and the National School Boards Association attempted to distinguish C.G.'s online speech from that of Levy's on the basis that it was “uniquely regulable” because it was “hate speech targeting the Jewish community”.

A three-judge panel of the Tenth Circuit unanimously rejected this argument. Judge Paul Joseph Kelly Jr., joined by Judges Scott Matheson Jr. and Carolyn B. McHugh, wrote that C.G.’s off-campus joke about “exterminating the Jews” would “generally receive First Amendment protection because it does not constitute a true threat, fighting words, or obscenity.” In a footnote, Judge Kelly added that “words as mere political argument, idle talk or jest” do not constitute “true threats”, citing United States v. Heineman, 767 F.3d 970, 972-973 (10th Cir. 2014).

“Defendants [the school district] cannot claim a reasonable forecast of substantial disruption to regulate C.G.’s off-campus speech by simply invoking the words “harass” and “hate” when C.G.’s speech does not constitute harassment and its hateful nature is not regulable in this context,” Judge Kelly concluded.

Why this Case Matters

Over the years, schools and public employers alike have expanded their definition of “discrimination” and “bullying” to cover not only violent threats and targeted harassment but also the mere utterance of politically incorrect viewpoints. Most institutions have spinelessly acquiesced to left-wing demands to enforce ideological conformity at the expense of freedom of speech and due process. It was inevitable that the excesses of progressivism would run into constitutional headwinds.

For decades, the judiciary has consistently held that “hate speech” is in fact free speech, even in an educational setting. Since the late 1980s, the federal courts repeatedly have struck down “anti-discrimination” speech codes, much to the chagrin of soys. See e.g., Doe v. University of Michigan, 721 F. Supp. 852 (E.D. Mich.1989); UWM Post v. Board of Regents of University of Wisconsin, 774 F. Supp. 1163 (E.D. Wis. 1991); Bair v. Shippensburg University, 280 F. Supp. 2d. 357 (M.D. Pa. 2003). As recently as 2021, the Sixth Circuit found that a college professor had a First Amendment right to “misgender” his students. Meriwether v. Hartop, 992 F.3d 492 (6th Cir. 2021).

Though C1.G. v. Siegfried considers the off-campus speech rights of high school students writing online (as opposed to the on-campus speech rights of college students and professors), the gist of the decision remains similar: it is not the place of educators to act as the social justice thought police.

All of these precedential First Amendment cases have important implications for American incels. Imagine if a 16-year-old boy was sitting at a cafe or in the town library after school, and a classmate inadvertently noticed his screen activity. Perhaps he was venting on Discord or Reddit or even our forum. “i hate my life all the foids at school are sluts who suck chads cock only” might upset a leftist school administrator, but as it currently stands, the U.S. Constitution bars public schools from disciplining a student for writing such a comment outside school hours.

For us, it’s a positive development that both the U.S. Supreme Court and now the Tenth Circuit have put overzealous school officials on notice: You may face legal consequences for trampling on your students’ constitutionally protected speech, even if a mob of pink-haired soys are triggered by “muh hates peach”.

Keep seething, cucks. These based federal judges have lifetime appointments and will be around for quite a while.